Closing her eyes, she clasps her hands. The maiko prays before the Shinto shrine. Her silver kanzashi hair ornament glitters. But her anxious posture shows how much she wants the kami to hear her plea.

Who is this anxious maiko?

Why does she pray for celestial comfort at this shrine?

The maiko is Yumehana (given name Nozomi), the TV drama is Dandan, and her anxieties center on dance. It has been a tough day. First, we saw Yumehana’s dance teacher harshly correcting her at the morning lesson. Next, we saw Yumehana’s rival, maiko Suzuno, taunting her at the evening party. Wickedly clever, Suzuno even maneuvered Yumehana into performing her weakest dance in front of clients at the party. Desperate to improve her dance skills —the maiko’s signature art—Yumehana makes her plea at Tatsumi Daimyōjin Shrine辰巳大明神神社.

Tatsumi Daimyōjin Shrine, petite and unassuming, sits right at the heart of Gion’s most photographed, picturesque location.

You will find the shrine at the foot of Tatsumi Bridge which spans Shirakawa (White River), a gentle stream. Old teahouses on one side of Shirakawa amid weeping cherry trees make this a picturesque sight. One of the most photographed in Kyoto, the scene calls to mind romantic notions of Gion’s past.

But what attracts maiko Yumehana here to pray for dance proficiency?

A little digging produced two important clues.

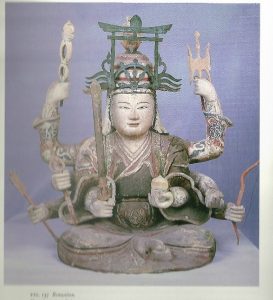

First, we learn that the kami of the shrine is Benzaiten 弁財天, who is “a deity highly popular among artists and musicians, as a patroness and guardian deity of the arts (Reader).”

Wooden sculpture of the goddess Benzaiten at the Hogon-ji Temple. Watsky, A. M. (2004). Wikimedia Commons

Wooden sculpture of the goddess Benzaiten at the Hogon-ji Temple. Watsky, A. M. (2004). Wikimedia Commons

Originally a Hindu deity, Benzaiten, also known as Benten, has found homes in Japan in Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines alike. She’s also one of the Seven Lucky Gods, “a multicultural, mixed gender, and religiously diverse group of deities who share the common cause of providing benefits to people (Reader & Tanabe,157).”

Next, we find that the sound “tatsu” in Tatsumi reminds us of the verb tatsu, “to improve one’s skill.” In fact, maiko and geiko really do pray for arts improvement at Tatsumi Daimyōjin Shrine, invoking Benzaiten’s blessings to “improve” their arts.

But Dandan does not leave everything up to Benzaiten.

When Yumehana’s mother, the successful geiko Hanayuki, catches sight of her daughter, viewers see her empathy. Hanayuki remembers battling the same anxiety in her own maiko days. But she faces Yumehana with practical advice and parental tough love, “Well, if that’s the case, then there’s nothing else to do but concentrate on your lessons every single day.”

The scene underscores one of the prime messages of Dandan—struggle against insecurity and work hard at achieving your goals.

Setting this exchange at Tatsumi Daimyōjin Shrine, Dandan acquaints viewers with this small Gion landmark, inviting us to find out about its history and the celestial comfort it offers to townspeople and artists alike.

Visitors to Kyoto can easily find Tatsumi Daimyōjin Shrine on tourist maps of the Gion. Shinto ceremonies are performed at the shrine four times a year by a priest from the much larger Fushimi Inari Shrine. The petite shrine is especially beautiful in spring when nearly covered by the weeping cherries.

Featured Image: Maiko Yumehana photographed near Tatsumi Daimyōjin Shrine. NHK TV Guide to drama Dandan, 2008. Japan Broadcasting Publishing Association.

References:

Gion Shopping Street Promotion Associates 祇園商店街振興組合 Japanese-language website: https://www.gion.or.jp/about/

Ian Reader. 2008. Shinto. Simple Guides series. Kuperard.

Ian Reader and George J. Tanabe. 1998. Practically religious: Worldly benefits and the common religion of Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawaiì Press.

Jan Bardsley, “Celestial Rescue for the Anxious Maiko.” janbardsley.web.unc.edu Sept. 29. 2020

This blog is for educational purposes only. I strive to locate and credit all sources and images cited here.

Nice post!

I like the interweaving of place and character. I hope that maiko improved her dance!

Isn’t the tatsu of tatsumi, dragon? Benzaiten often rides a dragon. Benzaiten is such a powerful deity! She presides over music, poetry, oratory–all things that flow–and also, if you’re lucky, the flowing of money into your pocket. (Her shrines are near water.)

Years ago I lived near Inokashira Park in Tokyo (near Kichijoji). Benzaiten is enshrined there on an island. I heard that it was dangerous for a woman to go there with her boyfriend b/c Benzaiten was a jealous goddess and she would do all she could to break up the couple’s relationship.

Lovers beware!

Very interesting on both counts, Rebecca! Indeed, tatsu, dragon, produces quite a monstrous kanji, I see: 龍

I guess if you can imagine all those strokes, all your wishes come true.

I didn’t know Benzaiten was so powerful. And yes, the maiko in this drama did learn to dance well, but only after she had gone through trials and tribulations that gave her a new maturity.

I love Inokashira Park!

May all kinds of good fortune flow into your life—and wallet.

Cheers,

Jan

Obviously I’m very late to the game, but I’d love to continue the conversation!

Another interesting thing to note is that, as the kanji for the shrine (辰巳) indicates, it is a shrine that is part of the fūsui (風水) or onmyōdō (陰陽道) system of directions and energy flows. The shrine’s original purpose, so it is said, was to protect the palace from the direction of the southeast (or “tatsumi” as it was then called). How long the shrine has been at this exact spot is not clear, but it does sit at a curve in the Shirakawa as it moves from north to south to the west, and this orientation — water flowing north-south, then turning to the southwest — was considered auspicious, so It’s possible that the shrine has been here a while. The Tatsumi daimyōjin shrine is also locally known as Gion Inari. It’s possible it got its “dragon” associations since the southeast direction was associated with the Azure Dragon (青龍).

Interestingly, there is actually a Benzaiten shrine about 300 yards almost due west from here, crammed in an area with outdoor seating and between shops and restaurants. I’ve never seen a maiko or geiko or anyone visit it.

These Shinto shrines are notoriously “slippery” and hence it seems nearly impossible to “nail down” any specific meanings to a shrine except how people use it — in this case for geiko and maiko to pray for getting better. Local businesses also use it like their Inari shrine to pray for better business.

Thanks, Gavin! How interesting about the energy flows and auspicious directions. I like your point about understanding these shrines from observing how people use them. Azure Dragon (青龍) sounds pretty cool.

Cheers, Jan

Hi Jan,

I enjoyed reading your post and I learned a lot from the comments. We can speculate freely about the name “tatsumi”. As Gavin commented, the presence of the shrine or temple is the most important for many Japanese, I guess. The character of deities in the shrine is not an essential reason for praying.

Thank you, Haruka. That’s interesting to know that the deity in the shrine is not as important for most visitors as the presence of the shrine itself.

I have always been curious about this pretty, petite shrine. Now I feel that I understand ways of thinking about it much better. So interesting to read everyone’s posts. Jan