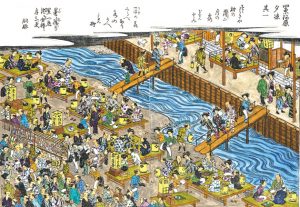

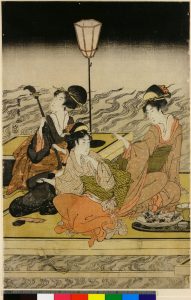

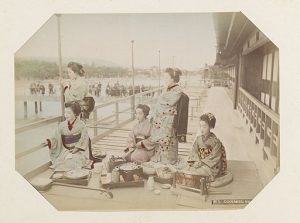

As Kyoto’s “dancing girl,” the maiko devotes herself to Nihon buyō (literally, Japanese dance).

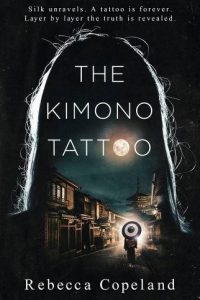

But how do others learn this dance form? What does it feel like to try? A riveting new murder mystery by Rebecca Copeland gives us clues.

Today’s post takes up Copeland’s debut novel, The Kimono Tattoo. We zoom into the mystery’s dance scenes, finding experiences much like those recounted by maiko and geiko.

From intriguing translation work to puzzling murder, Ruth Bennett is on the trail

But first, what’s the novel about?

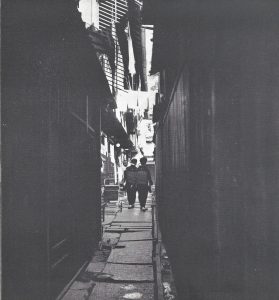

A fast-paced mystery, The Kimono Tattoo transports us to Kyoto. We wander into its famous temples, little known alleys, and even its zoo. Before we know it, we’re entangled in a shadowy web of beauty and deception.

We follow Ruth Bennett, a tall, red-haired American who parlays her fluency in Japanese into routine translation work. An avid runner, reader, and consumer of cheap Japanese take-out foods, Ruth works hard to maintain a low-key life. She wants to dull the pain of her past: a failed academic career in Japanese literature, divorce, and a haunting event in her youth.

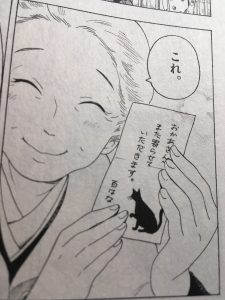

The mystery begins when Ruth cannot resist accepting a surprising offer. A stranger asks her to translate a new novel by a long-forgotten writer. That choice leads Ruth into all kinds of intrigue. She uncovers kimono secrets, family feuds, and ultimately fatal tattoo designs. Her life becomes anything but low key.

Once I started The Kimono Tattoo, I couldn’t put it down. I felt like I was back in Kyoto. I enjoyed the plot’s twists and turns. The characters really come alive. And Ruth’s own connections to her past in Japan become one of its driving forces. Her love of Japanese dance stood out to me.

The American teen finds her way in life through dance and kimono

We learn early on that Ruth is a student of Nihon buyō. This interest develops Ruth’s difficult past and her intimate connections to Japanese arts and kimono. Surprisingly, we find parallels to the maiko’s experience.

As a troubled fifteen-year-old stuck at a boarding school in Kobe, Ruth came to Nihon buyō at the suggestion of her Japanese language teacher. Taking up dance led Ruth to the kimono. She began regularly wearing kimono to her lessons, learning all the conventions. The entire experience was life changing. Ruth remembers, “I felt as if I had found something that belonged to me” (198).

Interestingly, Ruth’s sense of dance as a powerful channel for youthful angst mirrors comments by Iwasaki Mineko in Geisha, A Life. As a young girl newly living in an okiya in the 1950s, Iwasaki felt that, “dance was an apt vehicle for my determination and pride. I still missed my parents terribly and dance became an outlet for my pent-up emotional energy” (88).

Seeking solace as an adult, Ruth turns again to Nihon buyō and kimono artistry

Back in Japan after a divorce, Ruth takes weekly dance lessons in Kyoto. She puts together her kimono ensemble for each lesson with care. We learn how she selects just the right kimono from her collection to fit the occasion and express her mood. She knows kimono history and customs well.

As Ruth describes to a famous kimono designer, “The way the kimono is worn with an obi and other accessories tells me about the wearer’s taste, mood, or sense of daring” (203). Here, too, Ruth’s knowledge recalls Iwasaki Mineko and other geiko who describe their acute awareness of kimono customs, developed over many years.

Ruth’s Kyoto dance lessons

We never learn the name of Ruth’s dance teacher.

The sensei remains an enigmatic dancer–a brilliant artist and a demanding instructor. As Ruth says, “Nihon buyō teachers were particularly strict, and mine was no exception” (51). She does not suffer slackers. And she expects her students to prepare for their lessons and always come on time.

Maiko and geiko similarly remember the strictness of dance lessons. As Komomo explains in A Geisha’s Journey, “there were lots of rules to be followed at dance practice” (35). In her case, however, it was her strict elder sisters that scared her most at dance lessons.

Maiko inevitably make mistakes in their dance lessons, and Ruth slips up sometimes, too. She forgets her fan or music cassette. But, like maiko, she tries hard to please her teacher.

Through Ruth’s example, we learn dance lesson protocols. We see the greetings, the obligations, the importance of observing other students, and the sensei’s frequent corrections. We also get a glimpse of Ruth’s experience of dancing. Despite her early training, Ruth confesses that she has no “muscle memory” as an adult. “I felt like I had to start over from the very beginning” (53).

The teacher’s own dancing entrances Ruth. “She moved her hands lithely through the air, delicate but strong” (56).

Ruth sometimes has lapses in concentration, much to her teacher’s dismay. Of course, Ruth is involved in a murder mystery and that can be distracting.

The Perfect Summer Mystery

I highly recommend The Kimono Tattoo. Bringing to life a host of loveable characters (and some evil ones), The Kimono Tattoo weaves a compelling tale of beauty, love, greed, and revenge. It’s easy to visualize. Japanese dance, kimono, lore, and literature all contribute to the richness of its fabric.

Coming next: An Interview with Rebecca Copeland

How did the author’s own experiences shape the dance scenes in The Kimono Tattoo? What did she learn by studying Nihon buyō? Who were her teachers? In our next post, we sit down with Rebecca Copeland to get the answers.

How did the author’s own experiences shape the dance scenes in The Kimono Tattoo? What did she learn by studying Nihon buyō? Who were her teachers? In our next post, we sit down with Rebecca Copeland to get the answers.

References

Rebecca Copeland, The Kimono Tattoo. Brother Mockingbird, 2021.

Mineko Iwasaki and Rande Brown. Geisha, A Life. Atria, 2002.

Komomo and Naoyuki Ogino. A Geisha’s Journey: My Life as a Kyoto Apprentice. Kodansha International, 2008.

Jan Bardsley, “Dance, Mystery, and Murder in The Kimono Tattoo.” janbardsley. web.unc.edu May 27, 2021.