Marie Kondo’s method for sparking joy has made her a global super-star of tidying.

Today, I catch up with my friend and colleague, Japanese studies expert Alisa Freedman to talk about Kondo’s appeal.

In her superb new book, Japan on American TV: Screaming Samurai Join Anime Clubs in the Land of the Lost, Alisa Freedman gives in-depth analysis of Kondo’s media persona in Japan and the U.S. Let’s begin by meeting this prolific author.

Let’s Meet Author Alisa Freedman

Alisa Freedman

Professor of Japanese Literature, Cultural Studies, and Gender at the University of Oregon, Alisa Freedman is a well-known scholar, translator, and Editor-in-Chief of U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal. She’s given TED Talks, too.

Promoting Active Ways of Watching Television

Japan on American TV draws from a popular course Alisa has taught at University of Oregon. Taking a serious approach to TV in both the U.S. and Japan, she “strives to encourage debate and to promote active and critical… ways of watching television” (9). In Japan on American TV, she guides us to looking closely. What do you see in the frame? Importantly, Alisa shows how to connect these observations to their broader cultural and historical contexts and shifts in US-Japan relations.

What’s Marie Kondo’s Story in Japan?

JB: Good afternoon, Alisa, and thanks for sharing your thoughts on Marie Kondo. Reading Japan on American TV has sparked joy for me.

AF: Thanks, Jan. Great to talk with you today.

JB: Your writing about Marie Kondo reminds us that she had a career in Japan well before coming to Netflix. What’s her background?

https://konmari.com/about-marie-kondo/

AF: Kondo grew up in an affluent section of Tokyo, attending an old, elite Quaker school. Her fascination with tidying goes back to her childhood hobbies of reading homemaking magazines and straightening up almost every space she inhabited at home and school. She even wrote her college thesis in sociology at Tokyo Women’s Christian University on the topic.

Marie Kondo Draws from Many Streams of Thought

A Miko at Shimogamo Shrine, Kyoto. 2008. Wikimedia.

JB: What ideas shaped her tidying philosophy?

AF: Two important influences stand out in shaping Kondo’s thought–her interests in psychotherapy and Shinto. As I note in the book, Kondo’s reading in psychotherapy led her to perceive disorganization as a psychological condition. She also realized how ingrained the association between women and cleaning was in world societies.

Kondo’s affinity for Shinto dates to her days as an 18-year-old miko (shrine maiden). Although Kondo’s incorporation of Shinto is idiosyncratic, she borrows from its values of respect for one’s surroundings, rituals, and cleanliness.

Features of the KonMari Method

JB: What stands out about Kondo’s methods?

How to Greet Your Home

KonMari site. 2022.

AF: Kondo’s purification rituals and observance of rites of passage are grounded in Shinto. But her tidying method is premised on “Mindfulness” (derived from popular interpretations of Zen). She also draws on common sense and modes of Japanese cleaning (including those taught in Japanese elementary schools).

KonMari Core Ideas

Her method is a multistep process of assessing emotional attachment to objects, showing gratitude for what you have, and letting go of what no longer helps you.

Start by Sorting

According to Kondo, sorting belongings into categories and then choosing to keep only what “sparks joy” teaches us how to properly own things and to more comfortably inhabit our living spaces.

JB: Some have the impression Kondo is a minimalist. We find spoofs of her ideal place as completely empty. What do you think?

AF: She does not advocate “minimalism,” owning as few belongings as possible. Instead, she wants people to own things more intentionally. In fact, Kondo operates expensive online stores that sell a lot of knickknacks that might need to someday be tidied and disposed of when they no longer spark joy.

Winning Fame in Japan

JB: How did Kondo’s tidying career take off in Japan?

AF: In 2009, she started her own professional organizing business. She won first prize by writing about her tidying method for a contest sponsored by a self-help book publisher. That launched her career as an author.

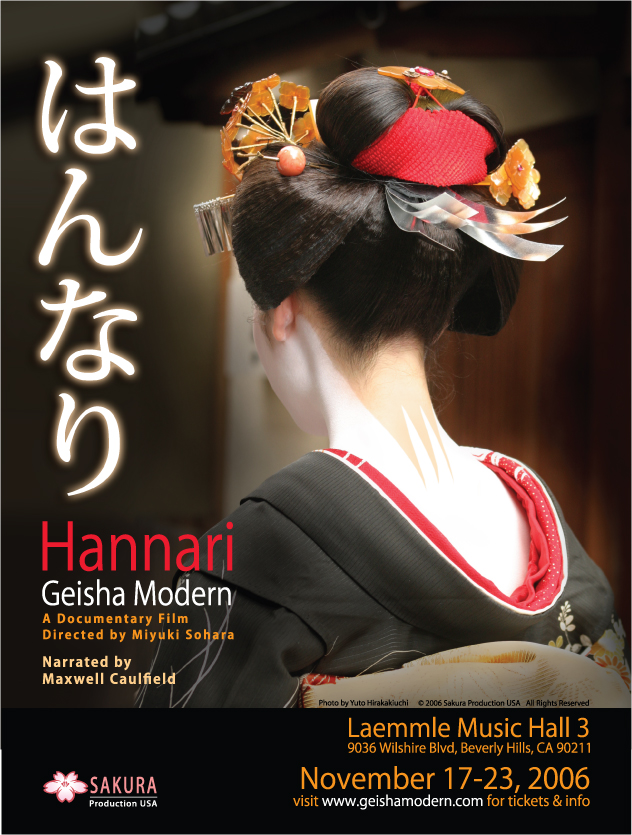

In 2010, this led to the publication in Japanese, and later English, of The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up. A global best-seller, it has been translated into around forty languages.

JB: I remember seeing the book everywhere in the 2010s! I’d meet people young and old who were folding their clothes in the KonMari style. I tried out some of the tips, too.

Marie Kondo as Yamato Nadeshiko

Dianthus Superbus. Stan Shebs. Wikimedia Commons. 2005.

JB: You describe Marie Kondo as enacting “Yamato nadeshiko”, an “ideal Japanese woman.” What does that mean?

AF: “Yamato” is an ancient term for Japan. “Nadeshiko,” a pink carnation, denotes a “gentlewoman.”

Yamato nadeshiko are devoted to the success of their families, their school team, or their workplace. They are demure but plucky, modest but strong.

https://epochtimes.today/marie-kondos-fold-clothes/

Yamato nadeshiko on Japanese TV often wear tasteful but simple clothing–usually skirts, dresses, or kimono. They have long dark hair with bangs and natural makeup. An approachable Yamato nadeshiko, Kondo chooses soothing colors. She often wears white cardigans. The cardigan suggests a kind of feminine professional note, and white conveys cleanliness.

Whether intentionally or not, Kondo engages the Yamato nadeshiko trope in her Netflix series. We see this not only in her appearance, but also in how she comports herself, interacts with American families, and incorporates elements of Japanese culture.

The American Aspects of Kondo’s TV Persona

JB: In what ways does Kondo incorporate American custom into her Netflix persona?

AF: Interesting question. In her Netflix series, she emphasizes her Japanese origins, speaking Japanese almost exclusively. But she smiles toothy grins, shows personal pride, and enjoys family displays of affection–all would read Americanized to a Japanese audience.

Reactions in Japan to Kondo’s Fame Abroad

Abe Books online.

JB: What was the reaction in Japan to Kondo’s global fame?

AF: Her appearances in Japan increased after her American success. Kondo’s business model provides a new transnational spin on the long-held belief that celebrity in the US is a road to success in Japan. Her Netflix series has been the most effective medium for mainstreaming her brand. For example, the popularity of the series drove traffic to Kondo’s other media, like her books, websites, stores, and KonMari Consultants training program.

The World of Professional Organizing

AF: Kondo is not the world’s first “professional organizer.” That is, a consultant offering guidance on how to organize things and declutter spaces. But she is the first to encourage global discussion and debate. Kondo has promoted international awareness of the job and has associated it with idealized Japanese women. Kondo uses her own original term “tidying consultant” perhaps to distinguish herself from other professionals in her field and to promote her distinct brand.

The number of professional organizers has increased in Japan and elsewhere, especially among women. This is thanks, in part, to the founding of organizations that foster community and provide information, resources, and certification programs.

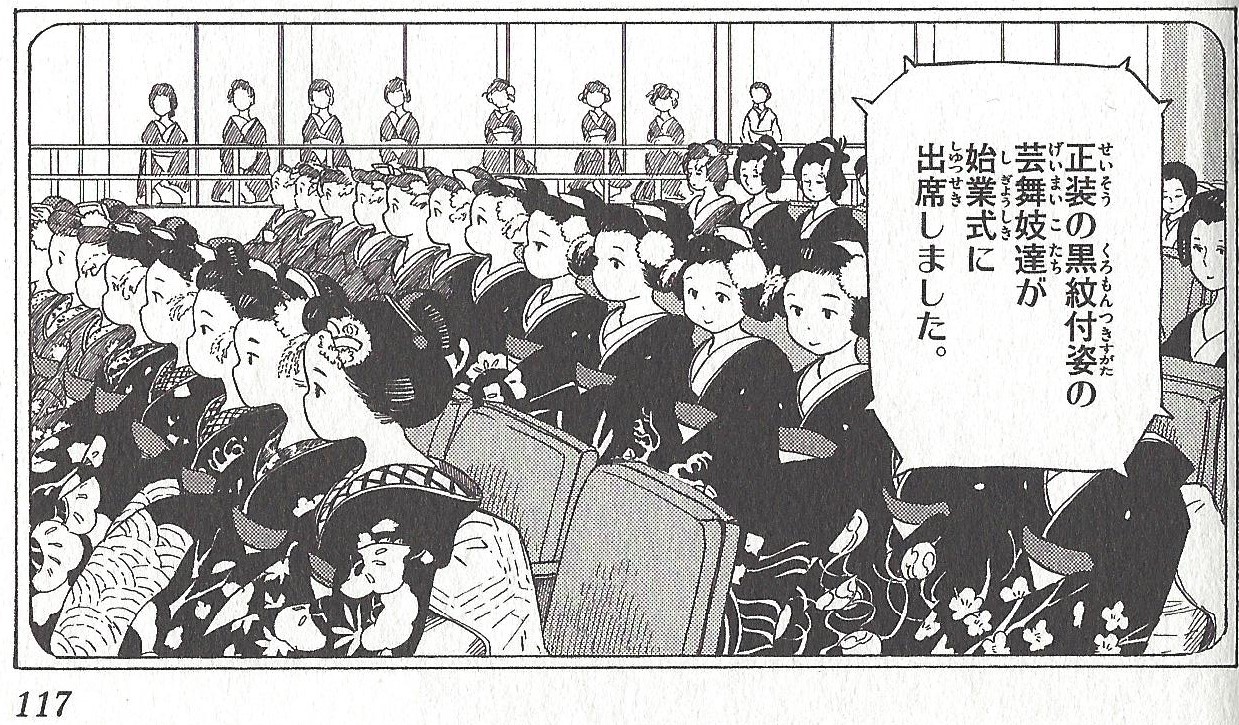

Criticism of Kondo’s Method

Some of these professional tidying organizations have offered the most profound critiques of Kondo’s method, even while expressing appreciation for the positive attention she has drawn to their profession. For example, JALO (Japan Association of Life Organizers, founded in 2008 to promote tidying as a way to learn life skills), has questioned the originality of Kondo’s method. Other groups have criticized the method’s rigidity and why tidying should only be accomplished in the order that Kondo proposes. Some Netflix viewers in the US and Japan took offense at things Kondo told her TV clients to get rid of, like books and mementos.

Online Memes Spoof the KonMari Method

50 Hilarious Reactions.

Mindaugas Balčiauskas.

Bored Panda.

AF: Online memes have parodied people throwing away mean bosses and others who do not “spark joy.” Or, giving up on tidying due to distractions or difficulties.

To the best of my knowledge, Kondo has not extensively responded to criticisms, modified, or updated her methods. These decisions might lead to her brand falling out of popularity. Kondo seems to learn little from her clients and, thanks to their adoration, remains convinced that her method of tidying is the only right one.

In her media, Kondo does not try to diagnose or treat mental health disorders like compulsive shopping or hoarding. Instead, tidying is shown to cure all. Perhaps unintentionally, Kondo promotes the belief that Japanese women prioritize homemaking and mothering, even as they balance careers and other aspects of their lives. I think many people in Japan view Kondo as an aspirational and Americanized celebrity and entrepreneur, rather than as representing all Japanese housekeepers.

Alisa Freedman’s Tips for Watching Marie Kondo on TV

JB: I know there’s so much more on Marie Kondo in Japan on American TV. But what three tips would you give to readers for watching Kondo’s Netflix series? What should we look for?

AF: You ask wonderful questions! Here are three tips–and one bonus tip.

Tip 1: Please think about how Kondo came to be on Netflix.

Doing so, reveals how American TV curates Japanese culture for international audiences while promoting ideas of US dominance.

For example, it is a little known fact that the Netflix series is based on a 2-episode Japanese NHK World TV series, Tidy Up with KonMari! (May 6 and 7, 2016), in which Kondo helps two female New Yorkers tidy their homes and thereby make room for new chapters in their personal lives. American TV producers also proposed making Kondo’s method the basis of a sitcom (2015) and a scripted program (2016).

Instead, producers combined a Japanese-made documentary for American audiences with conventions of American unscripted, highly-edited “makeover” reality programs. Taking this approach saved money (for example, on scriptwriting and acting) and created an appealing series that seemed both familiar and unique. The series was then dubbed and subtitled in world languages, including Japanese. Kondo has been the only celebrity to become a household name in the US by speaking Japanese on American television. Reflexively, her tidying method, promoted as representing mystical, Mindful, and minimalistic Japanese culture, has globalized in Asia and elsewhere in English.

Tip 2: Please watch how Kondo talks, gestures, and is positioned on screen.

All of this is intentional and shows how Kondo mobilizes stereotypes of Japan and Japanese women. For example, in each episode, Kondo arrives as a tranquil, foreign presence to heal American families suffering from domestic conflicts due to their inability to keep their homes in order.

She is filmed as if she is a mystical presence from a different, better, mysterious world. She speaks Japanese, with the exception of a few simple sentences like “I love mess,” and works through her interpreter, Iida Marie. While Kondo often sits on the floor while consulting and tidying, her American clients sit on chairs; this gives the unintended impression of people looking down at her. The families laugh when she cannot reach high places and make remarks about her size (under five feet).

Her cute gestures make her seem more accessible and less intimidating. Use of lighting and background music add to her calming presence. Kondo’s rituals, steeped in Shinto and Mindfulness, are both important components of her method. They also make great TV visuals for highlighting Kondo’s carefully constructed blends of cuteness and authority, “Japaneseness” and transnationalism. I will leave it up to you to find more examples of contrasts between Kondo and the Americans she mentors on Netflix.

Tip 3: I have learned how to be a better communicator and teacher by watching Kondo. Kondo attracts people because she seems likeable and is personable. On Netflix, she seems like a strict but enthusiastic teacher, reveling in her students’ successes. One reason the TV families follow her advice is because she is gentle and approachable, soft-spoken and patient, never yelling or scolding. Kondo is a carefully constructed yamato nadeshiko for American television and differs from reality stars who yell (Gordon Ramsey), seem aloof (Martha Stewart), or seem too peppy.

Bonus Tip: Kondo’s method takes practice and time.

Throughout the Netflix series, Kondo admits that she is not perfect: some things are out of place in her home; sometimes her children do not listen to her. Although it seems like Kondo’s TV families are making rapid progress, the show in reality is highly edited. Tidying piles make great visuals. Before and after shots encourage positive emotional reactions. To Kondo, the process of tidying is as important as the end result. That is why, she mentors clients rather than doing the tidying for them.

JB: Thanks, Alisa, for these insights on how to watch Marie Kondo on American TV.

AF: Happy to talk with you, Jan. Thanks for your interest.

More to Learn from Japan on American TV

It was fun talking with Alisa Freedman about Marie Kondo. There’s much more to learn from Japan on American TV. Alisa gives first-rate analysis of episodes of The Flintstones, The Simpsons, South Park, and King of the Hill, and even Sesame Street’s Big Bird’s adventure in Japan. We also learn about Japan in Saturday Night Live skits. Alisa includes a Watch List so readers can locate the episodes to watch on their own. She encourages us to draw our own conclusions before reading her analysis.

You can hear Alisa Freedman discuss Japan on American TV online, too:

Listen to Alisa Freedman’s podcast with Tony Vega on Japan Kyo: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e0vQZfSPgwY

Alisa Freedman participates with other Japan scholars in AAS Digital Dialogues: Japan on American TV. Online at: https://vimeo.com/647344516

REFERENCES

Balčiauskas, Mindaugas. “50 Hilarious ReactionsTo Marie Kondo That Will Bring You Joy.” BoredPanda.com. 2019.

Freedman, Alisa. Japan on American TV: Screaming Samurai Join Anime Clubs in the Land of the Lost. Asia Shorts, Number 11. Association for Asia Studies, 2021.

Tidying Up with Marie Kondo, Netflix, 2019.

Jan Bardsley. “Marie Kondo Sparks Joy on American TV,” janbardsley.web.unc.edu, January 24, 2022.