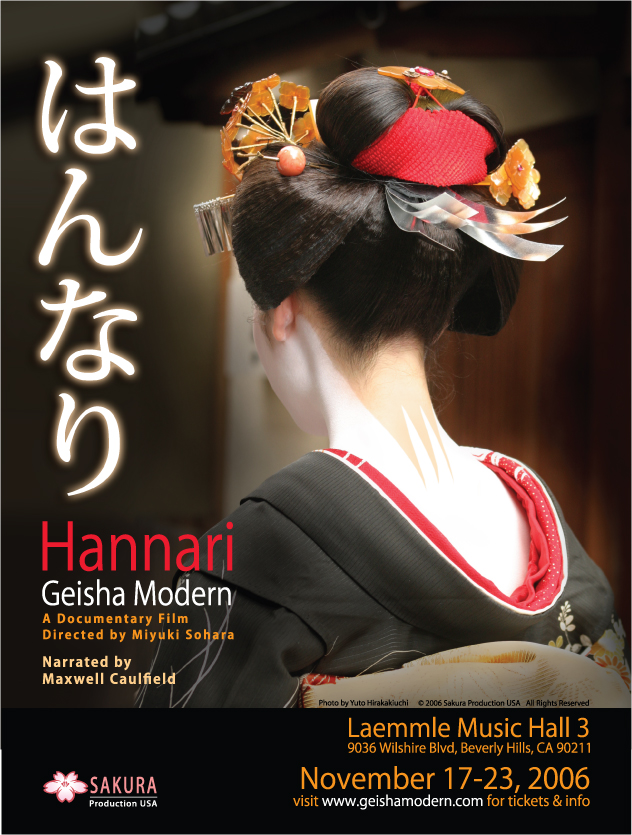

It’s wintry weather here in Chapel Hill. Perfect for movie viewing. This weekend I watched the documentary Hannari: Geisha Modern. Initially released in 2006, it’s now streaming on Amazon Prime. Today’s post reviews the film.

What Does the Word Hannari Mean?

Associated originally with Kyoto’s hanamachi, the word hannari suggests brightness, charm, and tasteful sophistication. (The film never explains its meaning).

Hannari: Geisha Modern succeeds in conveying respect for the hanamachi, its beauty, its traditions, and its fragility today. The “brightness” of the hanamachi comes across most strongly in the scenes of gorgeous dance productions. Yet, by emphasizing the rigor of hanamachi arts and etiquette, Hannari misses the jovial moments in teahouse culture. Like most documentaries on the hanamachi, this one, too, avoids any criticism of this world.

On a personal note: I enjoyed seeing many people in Hannari whom I interviewed while researching my book Maiko Masquerade. In fact, I received the Japanese DVD of Hannari as a gift from one of its geiko interviewees. I recognized others in the film from reading books about the hanamachi. Hannari reminds me of how small and tightly knit the community is.

Desire to Dispel the Memoirs of a Geisha Impression

Hannari’s emphasis on tradition and virtue over-corrects for the sexualization of geisha in the mass media.

Memoirs of a Geisha, the 2005 film adaptation of Arthur Golden’s novel, irked people in the hanamachi and its supporters. The creators of Hannari aimed to dispel its strong association of geisha and sex work. Hannari promotion underscores its accuracy, “Hannari – Geisha Modern is a documentary film that seeks to capture the geisha and their culture for what they are truly meant to be.”

Blogging about Hannari in 2007, Kyoto kimono producer Taizoh Takahashi expresses his strong distaste for Memoirs. He appeared in Hannari as a teahouse guest and later participated in some screening events.

Takahashi writes that Hannari director, Miyuki Sohara, a Japanese actress long based in Los Angeles, felt exasperated with Hollywood filmmakers’ sexualization of geisha. Like the geiko of Gion, Sohara, too, studied Inoue School dance. She knows its artistry and difficulty. Sohara and Takahashi felt inspired to make this film as a way to educate Americans.

No Oscar, but Many Endorsements from Japan

Aspiring for an Academy Award influenced Hannari’s length. Since the Academy requires documentaries be at least 90 minutes, Hannari, at 95 minutes, met that rule. But aiming for a lengthy documentary may have led to Hannari’s overly broad scope and lack of coherence.

Hannari did not win an Oscar. But the film’s homepage shows that it was screened widely in Los Angeles, and in San Francisco, New York, and major cities in Japan.

Its positive message about Kyoto’s hanamachi resonated well with many. The Prefecture of Kyoto, City of Kyoto, and The Japan Foundation have all endorsed Hannari.

Lovely Moments, Important Interviews in Hannari

What are the film’s strengths?

Hannari is visually beautiful. Lovely moments come in brief nature scenes of flowers and babbling brooks and closeups of quaint hanamachi streets.

Hannari devotes considerable attention to dance. We see the major spring productions at a distance and close-up. We can observe performers’ vivid costumes, facial expressions, and dance moves. Hannari captures the radiant display of ensemble numbers. We also see geiko and maiko dancing in the intimate venues of the teahouse for a few guests. Geiko Ichiyoshi’s dance rehearsal shows her maintaining perfect concentration despite the sweltering heat. These scenes will be valuable archival footage of well-known geiko and their performances.

Interviews with geiko of different ages and a few maiko are surely a strength of Hannari. I most enjoyed the interview with the late geiko Katsukiyo of Kamishichiken and her comic dance performance. I wish the filmmakers had devoted more time to these valuable interview opportunities and gone further into the veterans’ long lives in the hanamachi. Katsukiyo started attending teahouse parties at age 16 around 1945. This was a time of desperate poverty in occupied Japan. How did this context affect Katsukiyo’s early career? She also served as the long-time leader of the Kamishichiken district’s geiko association. What did this post entail?

Missed Opportunities in Hannari

Its overly broad scope, digressions, and stiff parties scenes weaken Hannari. Trying to do too much, the film misses the chance to tell a deeper, more coherent story about dance and the geiko’s life.

We see a truncated story of Gion’s famous Oyuki Morgan that ignores the ultimate tragedy of her 1904 marriage to a wealthy American. We spend too long at lackluster teahouse parties that center on self-absorbed men, rendering geiko and maiko passive. Apart from a solid interview with an unnamed specialist in crafting dance fans, the film skims over the contributions of many crafts people, perhaps a topic better left for a separate film. The digression into the museum-like preservation of the old hanamachi Shimabara does not fit well. At the end, the film descends into a kind of travelogue, explaining how the viewer might get access to the exclusive teahouse world or even visit Gion Corner to see maiko performing.

Hannari obfuscates the changes over time in the role of the danna (patron), conflating this with the contemporary sponsor. It does not take up how the geiko profession affected women’s private lives or social status outside the hanamachi.

Geiko and maiko often mention parents’ objecting to their daughters joining the hanamachi, even if the mother herself was a geiko. What were their objections? We never learn.

Too often Hannari gives male dance teachers the last word on the goals of geiko and maiko dancing. I wanted to hear more about what the women themselves felt about the experience, their favorite roles, and the difference between dancing on stage and in the teahouse.

Hannari Preserves Glimpses of the 21st-century Hanamachi

What might the perfect Hanamachi documentary provide? How can we encapsulate a living, breathing, growing, changing tradition—even in a film as long as Hannari? Although the documentary has its flaws, we are fortunate it has preserved even a slice of the rich cosmos of the 21st-century hanamachi.

Next Post: The February Setsubun Festivities

Setsubun festivities, marking a “seasonal division,” are among the liveliest in Kyoto’s hanamachi. Maiko and geiko take part in public rituals and teahouse party fun. Our next post explores these rituals and the carinvalesque costuming and comic acts that geiko perform that night.

Jan Bardsley, “Film Review of Hannari: Geisha Modern,” janbardsley.web.unc.edu, January 31, 2022.

Thank you for this review of the documentary Hannari. I haven’t seen it, but I’ve been cuarious about it.

So, does Hannari succeed in dispelling the The Memiors of a Geisha impression? I disliked the book, the movie, and the author, who didn’t care a bit about the accuracy or the feelings of the people portrayed.

Thanks, Aki. There’s nothing that suggests the geisha as femme fatale in Hannari. And there’s no mention of sex or romance at all, except to briefly mention Oyuki Morgan’s marriage. In that respect, Hannari does dispel Memoir’s focus on geisha and sex. If the movie had been 60 minutes and focused only on dance, it probably would have worked better. It is a very lovely film.

The history of Hanamachi is long, and it is such a complex and multifaceted world. So it is difficult to convey it in its entirety and all at once… I think it is important to have the intention of what part we want to transmit.

That’s such a good point. Even thinking of the difference between geisha, geiko, and maiko in the 1910s vs the 1930s vs the 1960s, we can see how the hanamachi culture changes amid tradition. Thanks for your comment, Haruka.