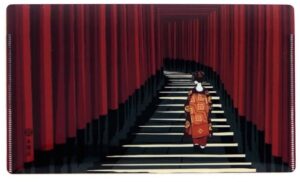

Bright ornaments (kanzashi) adorn the maiko’s hair in the early new year. The photo above captures Tomitsuyu wearing hers in 2015. Look closely at the base of the golden ear of rice on her right. You’ll see a tiny white dove. To the left, we see a cluster of small flowers.

What do these emblems of good fortune mean? The ear of rice, the dove, the cluster of flowers? Today’s blog explores these questions, taking us to maiko customs, a Japanese proverb, and the auspicious “three friends of winter.”

When do maiko wear the new year kanzashi?

Maiko wear these kanzashi when they attend their district’s Opening Ceremony and parties in the early new year. In Gion, the largest district, maiko wear these from January 7th through the 15th. Dates differ by district.

Let’s look first at the meanings attached to the ear of rice. In Japanese, the ear is called inaho (稲穂). Inaho is also used as a gender-neutral first name. By the way, the “ear” of rice refers to the “grain-bearing tip part of the stem of a cereal plant” (Thank you Google).

Rice seeds for good luck

Here we have an ear of unhusked, dried rice affixed to a long hairpin. A tiny white dove figurine sits at its base. (This one is a version for sale online.) Sometimes we see an artificial plum blossom placed at the base with the dove, too.

Maiko wear this kanzashi on their right. Geiko wear it on the left.

At parties in the new year, maiko and geiko give the seeds from the rice to clients. As the story goes, placing these seeds in one’s wallet makes your business prosper.

What values does the ear of rice symbolize?

「実るほど、頭を垂れる稲穂かな」

“The boughs that bear most hang lowest.”

Notice that Tomitsuyu’s ear of rice droops down. This recalls the Japanese proverb, “The boughs that bear most hang lowest.” Midori Ukita explains that ears of rice droop as they grow and ripen. The greater the number of seeds they hold, the more they bow. This combination of bounty and bowing evokes the famous proverb. That is, “the wiser a person becomes, the stronger sense of humility one develops.”

This fits the ideals taught to maiko and geiko. As artists, they realize that no matter how proficient they become in dance, there’s still more to learn. The inaho kanzashi expresses their resolve to remain humble while continually striving for improvement.

Bonds of Affection and the White Dove

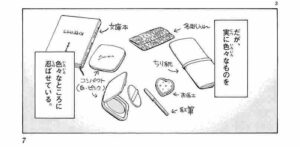

The dove figurine has no eyes. As the custom goes, maiko and geiko paint on one eye. Then, they ask someone they admire (or secretly adore) to paint the other. Supposedly, giving the dove eyes makes the maiko and geiko’s dreams come true.

Of course, this custom can cause difficulty. How does a popular maiko or geiko choose one among many loyal clients for the favor? No wonder, as Kyoko Aihara reports, some women just paint in the other eye themselves (38).

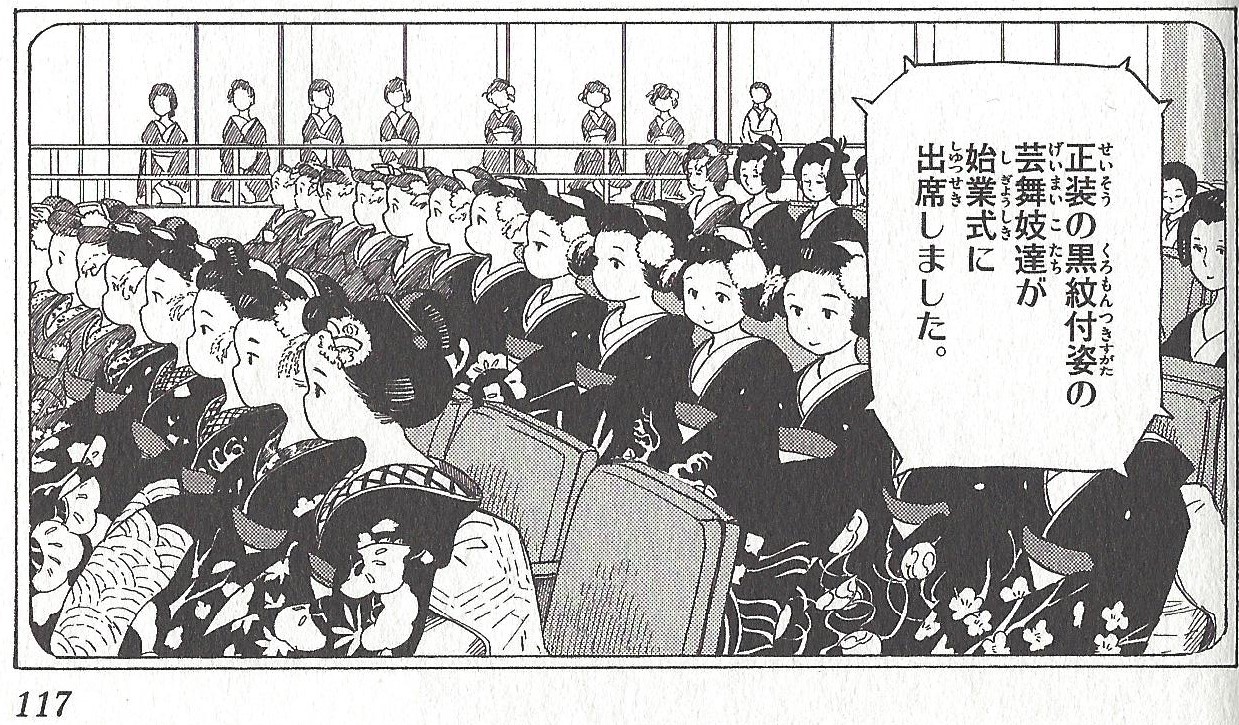

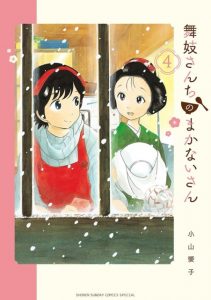

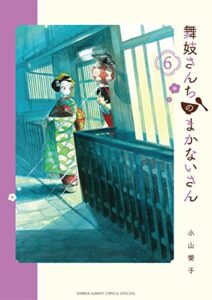

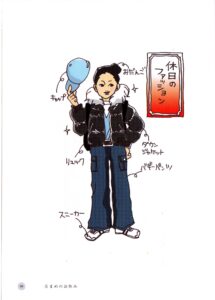

The dove-painting quest spurs drama in fiction. Here, we see Aiko Koyama’s star maiko Momohana contemplating her dove. Koyama also draws a group of maiko overly excited about getting one of their idols to paint the missing eye. They yearn to ask: a kabuki actor, a guitarist, a professional Japanese chess player, and even a secretly admired barista. Unbeknownst to the others and offscreen, Momohana chooses her best pal Kiyo for the honor.

The Auspicious Charm of Pine, Bamboo, and Plum Blossoms

Lots of color comes from the cluster of fabric ornaments. Here, they represent the famed “three friends of winter”– pine, bamboo, and plum bossoms–commonly associated with the start of the New Year. In Japanese, Shōchikubai 松竹梅. Due to “their ability to thrive even in the harshness of winter, pine, bamboo, and plum together embody steadfastness, perseverance, and resilience,” according to Princeton U. Art Museum.

But this example of a new year’s kanzashi is not the only one. In fact, the new year’s kanzashi design changes every year. You may see miniature versions of old-fashioned toys such as the spinning top (koma) and wooden paddles decorated with images of kabuki actors and geisha (hagoita). Kyoko Aihara notes that Winter Chrysanthemums have been popular in recent years (38).

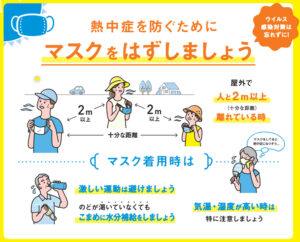

Making Connections to the Public Good beyond Maiko

The maiko’s new year kanzashi and participation in her district’s Opening Ceremony affirms her connection to community. I like the way Midori Ukita connects the humility of the inaho to our life in the pandemic. “The pandemic has served as a reminder that individual virtues are tied to civic virtues. We are humbled at this time and ever more aware that our personal sacrifices are connected to a broader public good.”

I hope to learn more about the maiko’s new year and her other kanzashi in 2022. I’ll post as I go.

FEATURED IMAGE: GION HIGASHI’S BILINGUAL TOMITSUYU

This 2015 photo of maiko Tomitsuyu is posted on the website of her small district Gion Higashi. Born in Kyoto, Tomitsuyu became a maiko in 2013 and a geiko in 2018. Having studied in New Zealand during middle school, Tomitsuyu is fluent in Japanese and English. https://giwonhigashi.com/sigyousiki2015/

REFERENCES

Aihara Kyoko. Maiko-san no Kyoto kagai kentei [The Maiko’s Kyoto Hanamachi Test]. Kyoto Shimbun Shuppan Sentā. 2021.

Koyama Aiko. Maiko-san-chi no Makanai-san. Serialized manga. Volume 3. Cover art. Shōgakukan, 2017. The White Dove (Episode 30) of the manga with English translation is available here: https://mangaboat.com/manga/maiko-san-chi-no-makanai-san/ch-030/

For its new online anime adaptation, NHK World translates the manga title as Kiyo in Kyoto: From the Maiko House. For New Year customs in the hanamachi, see Chapter 23: Opening Ceremony, Chapter 24: White Dove. Broadcast on September 23, 2021 Available until September 23, 2022. https://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/en/ondemand/video/2094008/

Ukita, Midori. NIHONGO Words of the Week (8). Japan America Society of Houston. May 11, 2020. https://www.jas-hou.org/weekly-nihongo/2020/5/11/nihongo-words-of-the-week-week-8

Jan Bardsley, “Adorned in Good Fortune: The Maiko’s New Year Kanzashi,” janbardsley.web.unc.edu, January 21, 2022.