As Kyoto’s mascots, maiko often welcome VIPs to the Old Capital. Maiko have greeted U.S. presidents, British royalty, and famed artists. But Godzilla? What’s behind this fantasy assignment?

Today’s post explores this Kyoto tourist campaign, its Godzilla goods, and ponders the imagined Maiko Godzilla face-off. We also reflect on these two Japanese icons’ journey from victims in the 1950s to cute ambassadors today.

Godzilla Comes to the Old Capital: Godzilla vs. Kyoto

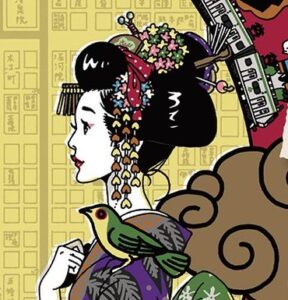

This eye-catching poster by Nakamura Yusuke promotes the 2021 tourist campaign Godzilla vs. Kyoto. https://gvskyoto.jp/

This Godzilla summer series of activities (stamp rallies; Godzilla film showings) takes one to various places in Kyoto. Stamp rally collectors visit Kyoto Station, Tōji Temple, and six places in the Kyoto Tower.

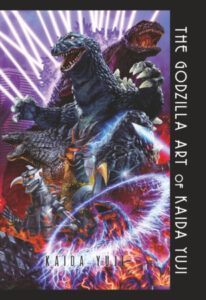

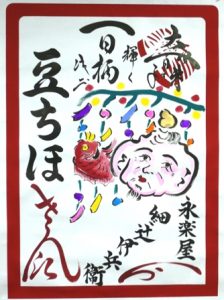

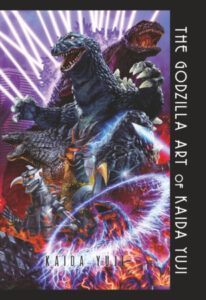

The Godzilla Art of KAIDA Yuji

By YUJI KAIDA. Titan Books, forthcoming October 2021.

Godzilla vs. Kyoto also features exhibits of original Godzilla-themed art by monster illustrators Yuji Kaida and Nishikawa Shinji. In April, the Kyoto International Manga Museum invited visitors to Nishikawa’s “live drawing” event.

Although the series opened in April 2021, it paused due to the pandemic emergency. Reopened, it has been extended through August. Organizers remind visitors to wear masks, practice social distancing, and avoid alcohol.

Godzilla Goods: Grooming the Monster Kyoto-Style

Towelette for Godzilla. July 2021.

The Godzilla towelette is just one of many goods devised by Kyoto businesses to sell during the Godzilla vs. Kyoto events. The typical towelettes (aburatori-gami) are slim, delicate papers. They fit easily in the palm of your hand. One uses them to remove make-up and blot facial oil.

About 33 times the size of the usual ones, these giant papers perfectly suit Godzilla. [Hard to imagine Godzilla feeling the need to get the shine off his nose, but he does have his close-ups]. Online at the Godzilla Store.

The towelette gives Godzilla hands-on experience with Kyoto tradition.

The Kyoto cosmetics store Yojiya claims to have sold the first towelettes in 1920. They quickly became popular with geisha and Kabuki actors who used make-up professionally. The Yojiya site remarks, “The circumstances of its creation could only have happened in Kyoto, the capital of Japanese cinema.” How fitting that Godzilla, a cinematic star himself, would enjoy a Kyoto towelette super-sized for him.

The Maiko Vs. Godzilla Face-Off

In Nakamura’s poster, Godzilla looks ferocious. He’s ready to snap off Kyoto Tower. Is he going to unleash his atomic breath on the maiko? Or ravish the beauty like King Kong? The maiko remains calm, meeting his gaze.

In Nakamura’s poster, Godzilla looks ferocious. He’s ready to snap off Kyoto Tower. Is he going to unleash his atomic breath on the maiko? Or ravish the beauty like King Kong? The maiko remains calm, meeting his gaze.

Nakamura’s poster suggests a sly Kyoto vs Tokyo competition. Kyoto has the winsome but fearless girl who embodies the movement of tradition into a modern sphere. Tokyo has the hideous monster, specter of modernity gone amuck. “No thanks!” the maiko seems to say. “Stay in your lane, Godzilla-kun. Hands off our tower.”

The Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympics, postponed to July 2021, offer an intriguing background. The Kyoto Tower, opened in December 1964, a couple months after the Tokyo Olympics. Tokyo may have a delayed Olympics this year, but Godzilla is visiting Kyoto and its Tower!

A Comic Diversion amid Olympic Concerns

Adorable monsters and tourists stroll across the bottom of Nakamura’s poster. They create a lighthearted pop cultural moment, moving freely in public after isolation. Here, sadly, the poster’s optimism belies the unabated spread of the pandemic in 2021, the slow roll-out of the vaccine in Japan, and opposition in Japan to holding the Olympics amid the pandemic. The monsters pose a cheerful deflection.

A Different Story of Godzilla and Maiko in the 1950s

Charming icons of cute today, the monster and the maiko represented quite different views of Japan in the 1950s.

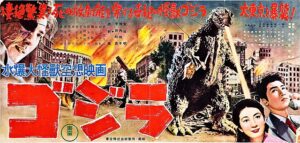

Godzilla 1954 Japanese poster. Wikimedia Commons.

The original 1954 Japanese film, pronounced Gojira, aimed for an adult audience. It carried a serious, anti-nuclear message. Godzilla was a peaceable, deep-sea giant who was mutated by U.S. hydrogen bomb testing in the South Pacific. The trauma causes him to rise and attack Tokyo (Tsutsui 2010). In 1954, Godzilla resonated in Japan with the traumas of war, defeat, occupation, and of course, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Also in 1954, Japanese fishermen aboard the Lucky Dragon suffered radiation poisoning amid U.S. nuclear testing on Bikini Atoll.

In the 1960s, however, in the era of Japan’s high-speed economic growth, Japanese Godzilla producers wanted to appeal to children. They tamed the monster’s image (Guthrie-Shimizu 59). Gerow observes that “Godzilla shifts from being a frightening beast to a fatherly hero defending Japan” (64). Between 1954 and 2004, Godzilla appeared in 28 Toho studios films (Tsutsui 2010: 79). Today, like Hello Kitty, Godzilla has become “camp/cool”; both are globally famous as Japanese icons (Yano 153).

Godzilla, Cultural Ambassador

1956 movie poster. Wikipedia.

As Tsutsui observes, Godzilla served as many moviegoers’ first introduction to Japan (2006: 2). The American adaptation, Godzilla, King of the Monsters!, debuted in the U.S. in 1956, billed as another among a spate of monster B-movies (Guthrie-Shimizu 52-53). Anti-American messages or serious reflections on nuclear issues were removed. Reflecting on Godzilla’s status as a long-time ambassador for Japanese popular culture, Tsutsui notes that a “1985 New York Times/ CBS News Poll famously found that the king of the monsters was one of the three best-known ‘Japanese people’ among Americans (2006: 2).

The Maiko’s Changing Representation

Gion Bayashi poster.

In the 1950s top-selling Japanese films about maiko represented her as victim, too. As I discuss in Ch. 4 in Maiko Masquerade, Mizoguchi’s 1953 film A Geisha (Gion bayashi), for example, depicts the maiko as harassed by clients and teahouse managers alike. Mizoguchi sees her world as beautiful and artistic, but also corrupt.

Maiko-san-chi no Makanai-san, manga by Koyama Aiko. 2017

Maiko tales of the 2000s tell a different story. The popular manga, now anime, Kiyo in Kyoto: From the Maiko House imagines a girls’ world of friendship and comfort foods. Like Godzilla in Nakamura’s poster, she, too, stands for playful Japan.

Toying with the Maiko Godzilla Face-off .

Toy icons. Chapel Hill, NC 2021

REFERENCES

For all things Godzilla, see the work of William M. Tsutsui:

Godzilla on My Mind: Fifty Years of the King of Monsters. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

In Godzilla’s Footsteps: Japanese Pop Culture Icons on the Global Stage. Co-edited with Michiko Ito. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

Japanese Popular Culture and Globalization. Key Issues in Asian Studies. Ann Arbor, MI: Association for Asian Studies, Inc., 2010.

Just a few of the provocative articles in Tsutsui & Ito’s co-edited book:

Gerow, Aaron. “Wrestling with Godzilla: Intertextuality, Childish Spectatorship, and the National Body.” 63-82 in In Godzilla’s Footsteps.

Guthrie-Shimizu, Sayuri. “Lost in Translation and Morphed in Transit: Godzilla in Cold War America.” 51-62 in In Godzilla’s Footsteps.

Yano, Christine R. “Monstering the Japanese Cute: Pink Globalization and Its Critics Abroad.” 153- 66 in In Godzilla’s Footsteps.

Jan Bardsley, “The Maiko Godzilla Face-Off,” https://janbardsley.web.unc.edu/ July 23, 2021.