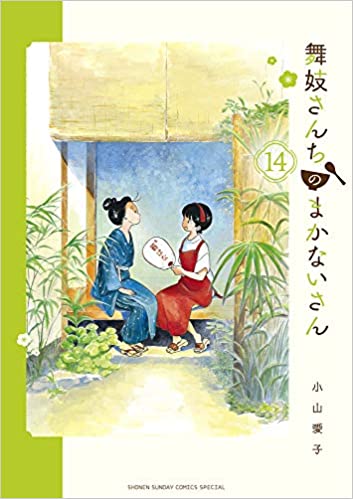

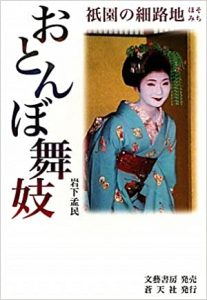

Learning about maiko customs takes us to many delightful Japanese things and their charming uses. Like the maiko’s thoughtful “stroke of a pen” notes that build friendships in the hanamachi.

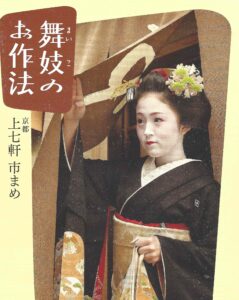

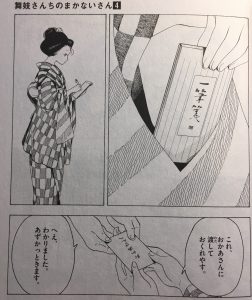

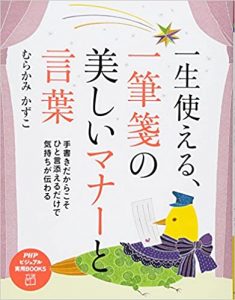

In her book Maiko Manners, Kyoko Aihara emphasizes how training by her arts teachers and her okiya mother develops the maiko’s poise. The apprentice also learns ways to use pretty Japanese products common in the past in her daily life. This enhances the maiko’s aura as a figure of nostalgia and tradition.

But, as Aihara also advises, readers can take tips from the maiko’s style to bring elegance into our own lives. Using kaishi 懐紙, a kind of Japanese paper associated with the tea ceremony, offers one way. Aihara shows many creative ways to use this lovely paper. Carry these in your handbag, she says, and you’ll find many unexpected uses, too (104).

Intrigued, I also searched online for images and videos. It turns out that there’s online videos that model a host of kaishi uses. They’re well illustrated, so you don’t need to know Japanese to understand them.

Today’s post introduces kaishi. I wrap up with a few attempts at trying these tips, too.

What are kaishi?

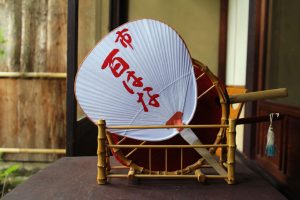

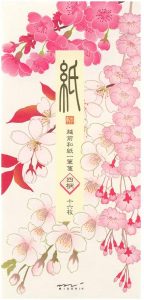

Kaishi for tea ceremony. Posted at Sazen: Peace and Harmony with the joy of tea. Accessed Mar. 20, 2022.

Kaishi are squares of Japanese (washi) paper. Made of natural fibers, they’re soft to the touch. And they’re absorbent. Kaishi are also strong enough to serve as an impromptu plate, bookmark, and for other creative uses, as we will see.

Searching various sites, I found lots on the role of kaishi in the tea ceremony. Packets of the plain white, folded paper are easy to purchase online. Apparently, they’re also gendered: men use a larger size than women do.

Kaishi in the Japanese Tea Ceremony

How do guests at a Japanese tea ceremony use kaishi? “Julia from Germany” explains in her photo essay for MIMARU Travel Guide.

Julia writes, “Upon bowing while sitting in the traditional seiza style, I was served a Japanese sweet on special paper called kaishi. I received a sweet dumpling called a manju. After I finished eating it, I tucked the kaishi into the breast of my kimono and a nearby woman started preparing the tea with a ritual to purify the utensils.”

Once “an indispensable tool” in Japanese daily life

Holmes of Kyoto. Vol. 7. Mai Mochizuki. Trans. Minna Lin. J-Novel Heart 2021. Posted to Goodreads.

Here’s a fun discovery. I found kaishi history in an unexpected source. In the light mystery novel, Holmes of Kyoto: Vol. 7, by Mai Mochizuki and translated by Minna Lin, one character explains:

“The word kaishi means ‘paper carried inside the kimono.’ Back when kimono were commonly worn, people would carry these around in everyday life. They were an indispensable tool that served the purpose of modern-day tissues, handkerchiefs, and note pads.”

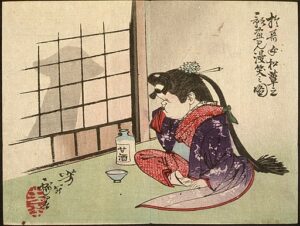

Geiko used kaishi creatively in the past, too.

Aihara explains how a geiko would twist a kaishi and wrap it around her little finger as a reminder. Seeing it, she’d recall, “Oh yes, my samisen teacher is coming at 3pm.” (107).

Kabuki actors used kaishi in certain roles. Kaishi also served those who wished to write a short poem.

But let’s get back to the present. How might we use kaishi today?

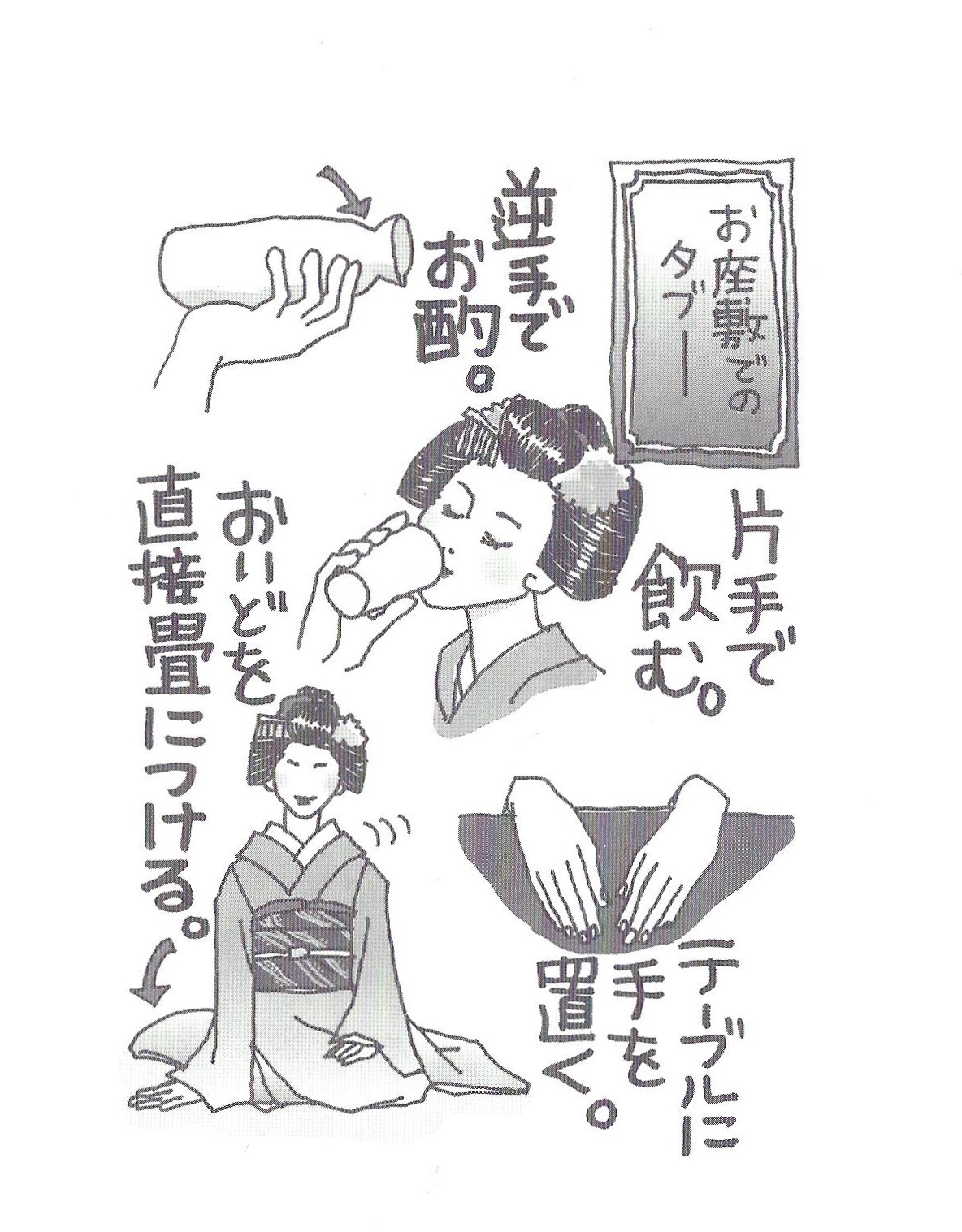

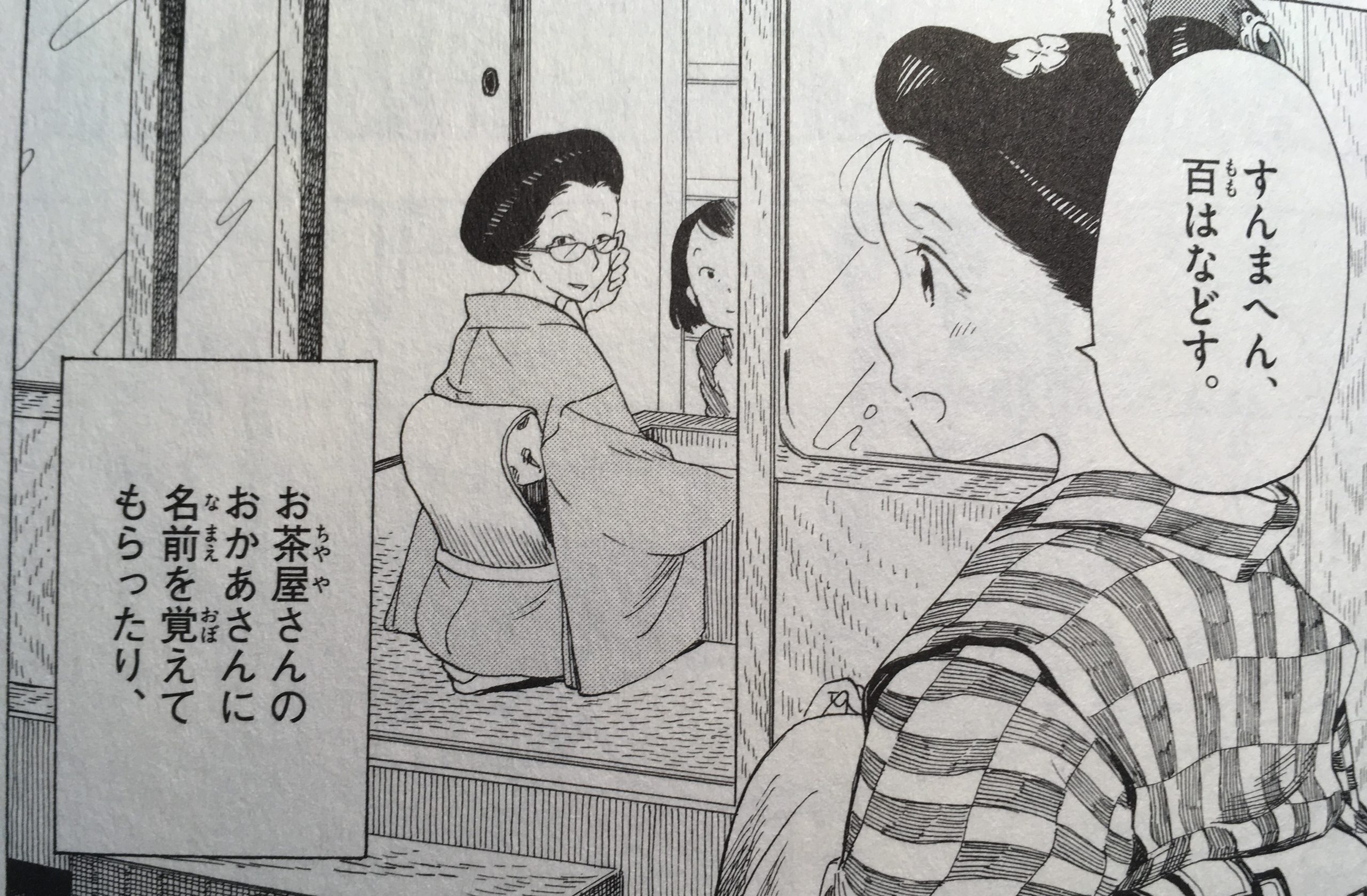

Maiko Manners & Kaishi

Macarons on kaishi. Posted to Hakkoubishoku. Oct. 10, 2010.

In Maiko Manners, Kyoko Aihara gives over 20 clever ways to use kaishi in daily life. Most aim to make little moments in dining lovelier and cleaner. One can imagine a maiko in her formal costume using these tips to maintain her “maiko-like” (maiko rashii) performance, as I discuss in Maiko Masquerade. Especially on outings to restaurants with favored clients.

What are some examples? You might fold a kaishi into a rest for your chopsticks or to brush off bits of food clinging to chopsticks. Use kaishi to wipe your hands or to clean dribbles on the table. Wrap chopsticks after use. Press kaishi against your mouth when you feel a cough coming one.

Want to show that you’re not having any sake at a party? Place your sake cup upside down on kaishi. A chic signal.

Aihara describes how in Germany, she happened to use a kaishi when eating a cookie. Curious, her German friends asked, “What’s that lovely paper?” Aihara uses this example to show how using kaishi, especially the kind with cheerful patterns, can give observers, too, a feeling of ease and comfort (107).

Kaishi make the practical pretty as memo paper

Aihara advises using kaishi for a quick message. Imagine you happen to visit a friend only to find she’s out. Just pen a short note on this distinctive paper to say you missed her. Tsujitoku of Kyoto recommends this as a chic practice, too.

It’s very fashionable to use kaishi for memos

–TSUJITOKU, Kyoto store website

Putting Kaishi Tips into Practice…and some failed attempts

My kaishi readings made me eager to try out these tips myself. I used kaishi that I had bought in Kyoto a few years back, but had no idea how to use. This packet of spring-green kaishi with chicks is the featured image today, too.

Use Kaishi as a Bookmark (shiori). This is an easy one!

Use Kaishi to Blot a Damp Brow. Hello Kitty Assists.

Kaishi for a quick “note to self”

Kaishi are perfect for wrapping cash tips. I enjoy following this Japanese custom, though I usually use small envelopes.

Kaishi — handy for eating fruit at a picnic lunch. (But maybe not for Sumo Mikan).

Guides to using kaishi advise placing fruit peels on the paper. Nice for a picnic lunch. I tried it with the fruit on hand, a Sumo Mikan. This seedless, sweet kind of satsuma orange is also called dekopon. Oops! Not the small fruit the kaishi guides show. Here, the poor chick looks distraught. The Attack of the Sumo Mikan!

The Fun of Kaishi

Online, we see many more ideas for bringing this bit of Japanese paper prettiness into daily life. Kaishi transform the humdrum and practical into moments of pleasure.

FEATURED IMAGE: Patterned kaishi purchased in Kyoto in 2019 at Washi Kurabu: http://www.washiclub.jp/ Washi Kurabu has a beautiful website, too.

REFERENCES

Aihara Kyoko. Gokujō sahō de miseru maiko-san manā-shū [Maiko Manners: The First-rate Etiquette that Enchants]. Sankaido, 2007.

Mochizuki Mai. Translated by Minna Lin. Holmes in Kyoto. Vol. 7.

J-Novel Heart, 2021. (The series is also in manga and anime formats).

Jan Bardsley, “Have Fun with Kaishi Paper, a Maiko Favorite.” Janbardsley.web.unc.edu. Mar. 31, 2022.