In early January, maiko return to Kyoto from their New Year’s holidays. What a change is in store!

Visiting with their families, they had a chance to let their hair down — literally. They wore casual clothes. They hung out with their old pals. And they relaxed into their local dialects. Back in Kyoto, it’s time to assume the maiko persona once more.

Let’s look at some comic scenes in the apprentices’ return to okiya life. They savor their last moments of vacation freedom and bring back tastes of home. These food souvenirs, called omiyage, represent an important gift-giving custom practiced throughout Japan. (That’s a topic for a future post).

Tasty Treats from around Japan

Arriving at their okiya, maiko share food gifts unique to their hometowns. Since the vast majority of maiko come from outside Kyoto, many different foods appear all at once. Each nicely wrapped.

For one example, our featured image (above) shows maple-leaf shaped Momiji manjū cakes. Filled with coarse red bean paste, they are famous in Miyajima (or Itsukushima) in Hiroshima Prefecture. Perhaps maiko hailing from Hiroshima would bring these to their okiya.

Describing the bounty of gifts, geiko Yamaguchi Kimijo writes, “It’s as though Gion turns into a department store of famous products from all over Japan. From the ends of Kyushu in the south to Hokkaido in the north” (128).

Maiko Must Return to the Hanamachi Dialect

Musing on the January return of maiko, Yamaguchi Kimijo observes their lapse into hometown dialects. Even after a short vacation, many find using the hanamachi dialect awkward. Kimijo hears odd intonations popping up as maiko try to get back into the linguistic swing of things. Their hometown dialects are as varied as the hometown foods. Still, the rhythm of hanamachi life soon resumes.

“There’s a point when the famous local specialties from all around Japan and the hometown dialects, too, have disappeared.

That’s when the new year has truly come to Gion” (129).

Koyama’s Maiko Enjoy Hometown Food Gifts, too

Imagining the maiko’s return, manga artist Aiko Koyama shows them fascinated with each other’s food gifts. These maiko munch on all sorts of goodies and take pride in their hometown foods. “That’s mine, from Hokkaido.” “That’s mine, from Hiroshima.”

Maiko Momohana and Friends Catch a Fast-Food Break

Aha! The food action in this manga story takes a new turn when their okiya mother gives the maiko money for a last hurrah of fast food. Off they go in their casual clothes! Once in their maiko hairstyle and kimono, they should not be seen in this contemporary realm of convenience.

At the fast-food place, they meet newly returned maiko from other okiya, too. A flurry of greetings ensues.

Maiko Momohana suggests that her group take their teriyaki burgers down to the bank of the Kamo River. It’s super windy and cold. But Momohana appreciates the chance for them to gather incognito. Since they are dressed casually, no one knows they are maiko. As a result, they can enjoy watching others instead of standing out themselves.

A Taste of Teenage Freedom

Koyama depicts even proper Momohana and cook Kiyo enjoying every bite of the huge sandwiches. Looking at her juicy burger, another girl says, “Well, I guess today I’m not back to being a maiko yet.”

The Quest to Become a Maiko-like (maiko-rashii) Maiko

These comic moments of maiko reverting to their hometown teenage selves reminds me of the flip side—their ongoing quest to become maiko-rashii maiko.

As we see in Maiko Masquerade, contemporary maiko fiction plays with the idea of the backstage maiko striving to squelch her appetite to perform as the ideal apprentice. The fiction trains us to admire the maiko’s work, her successful maiko-rashii moments, and empathize with her struggles. No doubt these moments remind us of our own efforts to conform to a public role. After vacation, we, too, must once again assume our professional persona and get to work.

Formal New Year Beginnings: The Opening Ceremony

Of course, formal rituals and costume help the maiko switch back into her apprentice persona.

As we saw in earlier posts, Gion Kōbu and other hanamachi hold their annual Opening Ceremony. All the maiko and geiko dress formally, and the maiko wear a veritable bouquet of hair ornaments (kanzashi). It’s quite a sight to see them proceed through the hanamachi to the ceremony.

This glimpse into the backstage helps us appreciate the work ordinary girl must do to get in gear for the new year and perform maiko-likeness.

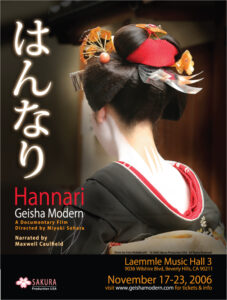

Next Post: Documenting the Hanamachi: Film Review of Hannari: Geisha Modern

Today’s post explored the comical side of hungry maiko backstage. In our next post, however, we look at filmmaker Miyuki Sohara’s attempt to capture the serious side of hanamachi culture. We consider the film, Hannari: Geisha Modern.

Featured image: “Food in Miyajima, Hatsukaichi, Hiroshima, Japan.”

Posted by Daderot, 2001. Wikimedia Commons. This lovely photo features Momiji Manjū Cake.

REFERENCES

Koyama Aiko. Maiko-san-chi no Makanai-san. Serialized manga. Volume 3. Shōgakukan, 2017. “Kyoto, Once More” (Episode 27) of the manga with English translation is available online: https://mangaboat.com/manga/maiko-san-chi-no-makanai-san/ch-027/

Yamaguchi Kimijo. Suppin geiko: Kyoto Gion no ukkari nikki [Bare-faced

geiko: My haphazard diary of Gion, Kyoto]. Tokyo: LOCUS, 2007.

Jan Bardsley, “Backstage with Hungry Maiko in Early January,” janbardsley.web.unc.edu, January 27, 2022.