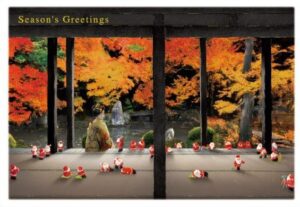

February 25th is a busy day for women in the Kamishichiken hanamachi. Clad in formal kimono, maiko, geiko, and teahouse managers serve tea to numerous guests. All to celebrate the Plum Blossom Festival (Baika-sai) at Kitano Tenmangū Shrine.

How do maiko dress for the event? What’s the meaning behind this festival? Today’s post takes a look.

The Discover Kyoto website has spectacular photographs and a video of the event.:

https://www.discoverkyoto.com/event-calendar/february/baikasai-kitano-tenmangu/

Maiko Dance & Greet the Public

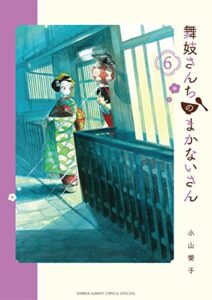

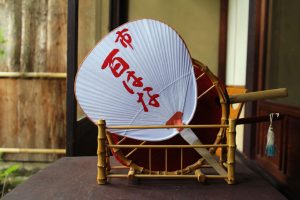

The image above shows a maiko at the festival wearing the February kanzashi hair ornament. It follows the plum motif, too. A cluster of fabric blossoms in red, white, and pink. In various photos of the event, I notice some maiko wear kimono with plum blossom patterns.

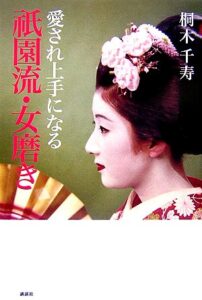

The photo shows the maiko participating in the festival’s open-air tea ceremony (nodate) at the shrine. It’s been performed annually since 1952. As the Discover Kyoto clip shows, maiko, geiko, and teahouse managers work together to serve the tea. Friendly and formal, the women manage to serve hundreds of guests. Due to pandemic precautions in 2022, however, they will perform a tea ceremony, but not do the public service (Sharing Kyoto).

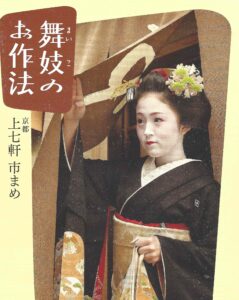

Kamishichiken maiko Ichimame describes how performing at Baika-sai offers a chance to show how she has progressed in her arts practice. “When we bring the tea, everyone looks truly happy, and that makes us feel pleased, too” (34).

Whom does the festival honor?

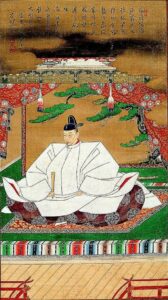

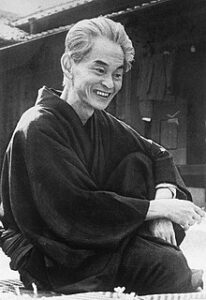

Portrait of Sugawara Michizane, Japanese. Muromachi period, 15th century, ink and color on silk, Honolulu Museum of Art. Wikimedia Commons.

The festival takes place on the death anniversary of Sugawara no Michizane (845-903). The legendary Heian scholar of Chinese literature wrote poetry in Chinese and Japanese. As a civil servant, he rose to a powerful position at court. Accused of treason by a rival, Michizane found himself banished from court. He was sent to an administrative post in Kyushu where he later died.

But a series of disasters struck only two years after his death. Was this a sign of Michizane’s vengeful spirit? Efforts to appease his spirit led to restoring his title and recognizing Michizane as the heavenly diety (tenjin) of learning. The year 947 saw Kitano Tenmangū Shrine erected in his honor. The Kitano website states, “There are as many as 12,000 shrines that are dedicated to Sugawara no Michizane in Japan, but the Kitano Tenmangu Shrine is the origin and the main shrine.” Hoping for success in their own exams, students travel to Kitano Tenmangū Shrine with their prayers to this diety of learning.

The Baika-sai festival commemorates Michizane’s fondness for plum trees.

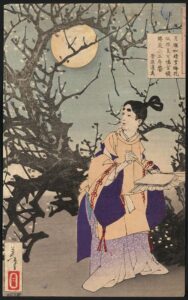

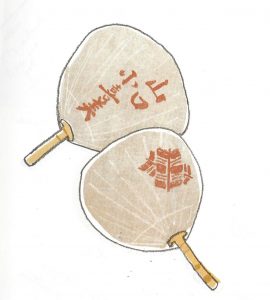

Yoshitoshi’s print (above) captures Michizane, the poet, enthralled with the sight of plum blossoms. The Claremont Colleges Digital Library explains its context.

“The plum blossom was Michizane’s favorite flower, and he would often write about its fragile petals and delicate fragrance. Here the artist has depicted the young poet writing on a folded sheet of paper held on a fan. The gnarled plum tree trunk is rendered in strong calligraphic strokes, which suggest the powerful brushwork for which Michizane would become famous.”

Homage to Hideyoshi’s Famous Kitano Grand Tea Ceremony

The tea ceremony at Baika-sai also pays homage to another famous figure in Japanese history, the warlord Hideyoshi Toyotomi (1537 – 1598). He held the Grand Kitano Tea Ceremony at Kitano Tenmangū Shrine in 1587. Since the teahouses near the shrine served as resting places for Hideyoshi’s spectacular event, this may be the origins of the Kamishichiken hanamachi.

Plum Blossoms Past and Present

The annual Plum Blossom Festival at Kitano Tenmangū Shrine gives the public a chance to see maiko and geiko. They bring the past to the present through costume, dance, and tea ceremony. The festival recalls legends of the past, the blossoms coax one to enjoy the moment.

Next Post: Hello Kitty!Hello Maiko!

Next week, we celebrate Girls’ Day and the Doll Festival (Hinamatsuri) in Japan.

What do playful icons of maiko and Sanrio’s “Hello Kitty” character have in common? How about when Kitty-Chan performs in Maiko cosplay? What’s the difference between these two as dolls of contemporary Japan?

FEATURED IMAGE: Lovely photo posted in 2011 by 663highland to Wikimedia Commons. It’s taken at Kitano Tenmangū in northeast Kyoto.

REFERENCES:

“Baikasai and Nodate Ohchanoyu (Ume plum blossom festival).” Sharing Kyoto.

Feb. 08, 2022. https://sharing-kyoto.com/event_Plum_Festival

Kamishichiken Ichimame. 2007. Maiko no osahō (Maiko etiquette). Tokyo: Daiwa Shobō.

Jan Bardsley, “Maiko at the Plum Blossom Festival,” janbardsley.web.unc.edu, February 24, 2022.