Who was this happy little girl in maiko cosplay?

The beloved manga character Chibimaruko-chan.

Today I catch up with manga scholar Hiromi Tsuchiya Dollase (Vassar College) to find out more about this likeable character. What’s the story of this delightful girl and her appeal? How does she fit easily into the girls culture represented by contemporary maiko?

Indulge in a perky musical warm-up

But first, let’s warm up by listening to the toe-tapping theme song for the animated version:

Imagining the 1970s middle-class family in Japan

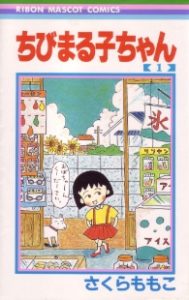

Chibimaruko-chan, an enormously popular manga, ran about ten years from 1986-1996. Initially serialized in the girls’ comic Ribon, it was transformed into anime in the early 1990s. You can find versions of the anime subtitled in English online, as in the warm-up example.

But manga artist Sakura Momoko sets the comic in the 1970s. Why choose the 1970s?

Nostalgia as healing

For one reason, Sakura Momoko (1965-2018) came of age in the 1970s. The comic re-imagines her own middle-class upbringing in Shizuoka, the lovely seaside city near Mt. Fuji. The 1970s setting also has sparked pleasant memories for many fans. During the fast-paced, high-octane life of the affluent 1980s, Dr. Dollase reasons, readers found moments of relaxation and nostalgia in the charming comic of ordinary middle-class life.

“The manga presented values which were different from the money-centered values of the 1980s bubble economy era. Chibimaruko-chan always provided readers of that time with a sense of comfort, peace, and iyashi (healing),” says Dr. Dollase.

Chibimaruko as a girl with a mind of her own

Who is the lead character? The artist names her eight-year-old character after herself: first name, Momoko; family name, Sakura. But as the manga frame above explains, everyone calls her Chibimaruko. Literally, her nickname means “little” (chibi) “round” (maru) girl. (Chan is a familiar suffix often used for children).

Dr. Dollase views the name as showing acceptance of petite Japanese bodies that often differ from the tall, willowy Anglo bodies promoted in global fashion media. As chibi, the girl is kawaii, too, suggesting vulnerability and the need for protection. She can both speak her mind and remain childlike.

But, Chibimaruko-chan is not the little princess typically found in comics for girls (shōjo manga). Princess girls favor frills, western-style furnishings, and everything feminine. In contrast, Chibimaruko-chan is precocious. She can be sloppy and lazy. She’s a daydreamer. Her habit of procrastinating gets her in trouble. But these flaws, too, are part of her appeal.

“An interesting thing about the Chibimaruko-chan comic is that each person reads it differently. Small kids might enjoy it because the characters in Chibimaruko-chan are cute, funny, and goofy,” explains Dr. Dollase.

The cartoon also had broad appeal across age groups.

The broad appeal of Chibimaruko-chan

Dr. Dollase remembers, “I enjoy reading Chibimaruko-chan because it reminds me of my childhood growing up in the 1970s. I read this comic in real-time when it was serialized in Ribon (comic magazine). At that time, I was a college student.” She recalls how different the character seemed. “At first, I was shocked by this manga, because it was so un-shōjo-like. But I quickly became a fan.”

In her insightful chapter, “The Cute Little Girl Living in the Imagined Japanese Past: Sakura Momoko’s Chibimaruko-chan,” Dr. Dollase explains the history and appeal of the popular character. She notes how Chibimaruko enjoys a home life that conveys affection, equality, and belonging.

Watching video clips, we observe how artist Sakura Momoko uses iconic images of the healthy 1970s family. The Sakura family gathers around the low-table in their Japanese-style living room. Here, they eat, talk, and watch TV together.

Dr. Dollase writes, “Chibimaruko-chan provides readers with a warm and comfortable space in which they feel protected, at home, and more importantly, happy to be Japanese” (42).

Yet, this is the “imagined Japanese past.” It is one that excises references to social problems. For example, the growing problem of environmental pollution caused major concern in the 1970s. By the same token, American TV created much the same images of familial innocence in the 1950s and 60s. White, middle-class families featured in shows like Father Knows Best (1954), Leave it to Beaver (1957), and My Three Sons (1960).

A new kind of Japanese father

Dr. Dollase also points out how the friendly father-daughter relationship in Chibimaruko-chan reflected actual changes in the family structure amid growing affluence. Mothers took on more power in the home in the 1960s and 1970s as many men spent long hours away from home. The stereotypical salaryman’s life revolved around his commute, work, and company leisure activities.

Once conceived as cranky, powerful patriarchs, fathers took on new positions in 1970s comics. Sometimes they were almost out of the picture. Artist Sakura Momoko, however, uses the fantasy power of manga to imagine a positive father-daughter relationship, one that would appeal to girl readers. Mr. Sakura is an “affectionate, friend-like father” (45). Dr. Dollase remarks that this exploration of father-daughter relationships marked an innovative feature of this 1980s comic despite its 1970s setting (45).

The happy bubble of girls’ culture

Dr. Dollase imagines it was the inviting power of girl culture that attracted fans. “The world of Chibimaruko-chan is a young woman’s protected ‘bubble’ that provides her with coziness, confidence, and a sense of belonging” (46). In much the same way, manga and fiction about maiko create a girls’ world, too, portraying girlhood as a time of freedom and discovery, one that everyone can retrieve through enjoying these fantasy characters. Charms, like the Chibimaruko-chan maiko strap, happily transport us there.

“I see many similarities between Chibimaruko and maiko. The Chibimaruko/Maiko ornament that you included on this page is so cute and perfect! I think that Chibimaruko and maiko are catalysts for girls and women’s imagination,” says Dr. Dollase.

“I see many similarities between Chibimaruko and maiko. The Chibimaruko/Maiko ornament that you included on this page is so cute and perfect! I think that Chibimaruko and maiko are catalysts for girls and women’s imagination,” says Dr. Dollase.

Thanks, Dr. Dollase!

Thanks very much to Dr. Hiromi Tsuchiya Dollase for participating in today’s blog post. For more analysis, I recommend reading Dr. Dollase’s chapter on the topic and her book Age of Shōjo. And maybe take a trip to Chibimaruko-chan land, too.

References

Dollase, Hiromi Tsuchiya. “The Cute Little Girl Living in the Imagined Japanese Past: Sakura Momoko’s Chibimaruko-chan.” In International perspectives on Shojo and Shojo Manga: the influence of girl culture, edited by Masami Toku, 40-49. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Nippon.com, “Sazae-san” and “Chibi Maruko-chan”: Two of Japan’s Most Beloved Anime,” https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-glances/jg00124/sazae-san-and-chibi-maruko-chan-two-of-japan%E2%80%99s-most-beloved-anime.html, accessed April 11, 2021.

For more on the shōjo characters in Japanese fiction, I highly recommend Hiromi Tsuchiya Dollase’s book, Age of Shōjo: The Emergence, Evolution, and Power of Japanese Girls’ Magazine (SUNY Press, 2019).

Jan Bardsley, “Girls Culture Mascot Chibimaruko-chan, as cute as a maiko,” janbardsley.web.unc.edu, April 12, 2021.