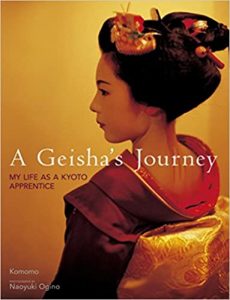

What does this maiko carry? It suits her silky formal costume perfectly. When does she use this bag? What does she carry inside? We explore all these questions in today’s post.

But then, we take things a step further. We look at the fascination with the contents of women’s handbags more broadly. If the handbag offers a window into a woman’s personality, what does the maiko’s kago say about her?

What is a maiko’s kago?

The maiko in our featured photo carries an ozashiki kago. It’s a kind of handbag assembled from a drawstring cloth attached to a long, woven basket-base or kago. Maiko carry these when wearing their formal kimono to ozashiki (teahouse parties). Hence, the formal name ozashiki kago, or for short, simply kago.

How do kago suggest the seasons?

Kyoko Aihara (2011) explains how the choice of textile for the kago, and its color and pattern, can signify the season. These choices can also indicate the maiko’s maturity in her apprenticeship.

In winter, the kago will have a dark base, like the one Momohana carries here in February. The fabric might be chirimen (silk crepe). The fabric’s images might be lucky items (takara zukushi), spinning tops (koma), or the wooden paddles (hagoita) associated with the old New Year’s game.

In the summer, the maiko’s kago will feature fabrics like linen or silk gauze. The woven base remains natural. Patterns on the fabric will suggest summer, employing images of morning glory, fireworks, or fireflies. But, as Aihara reminds us, kago patterns are not exclusively seasonal (119).

As the maiko matures, the color of the kago fabric changes. Aihara observes that at her debut, the maiko may carry a kago featuring bright red chirimen. As she matures, the maiko may use blue or yellow-rose fabric, for example (120).

Maiko etiquette: Proper kago use at the teahouse

Manga artist Aiko Koyama introduces her readers to the maiko’s use of kago.

In this episode of Koyama’s popular girls comic, animated as Kiyo in Kyoto, we see trainee Rika carrying Momohana’s kago for her as they walk one evening to the appointed teahouse. At the entrance, Momohana takes the bag. But, as we see in this frame, when Momohana enters the teahouse, she asks to leave her kago in the okami-san’s office downstairs. This follows custom as maiko and geiko do not bring kago into the ozashiki.

Even cosplaying “maiko” carry kago

Maiko cosplay gives tourists a chance to play with kago fashion. Photo studios in Kyoto sometimes add kago to the cosplayer’s maiko outfit.

The studio dressers show the correct way to carry it. Here, the young tourist on the left carries one with a red and white pattern.

Fascination with what’s inside handbags

When I searched for images of the maiko’s kago, I happened on lots of videos, stories, and studies of the contents of women’s handbags.

I even discovered an inviting museum in Little Rock, Arkansas devoted to the topic: Esse Purse Museum, founded by Anita Davis. Intrigued, I read Esse’s What’s Inside? A Century of Women and Handbags, 1900-1999. Davis writes, “The purse holds power” (10). Inside the woman’s handbag, we find, “hints about her identity…and what she chooses to carry” (10).

British Vogue presents In the Bag, short, comic, online videos with celebrities showing the contents of their handbags. Emma Watson, Serena Williams, Helen Mirren, and others laugh at their surprise discoveries or the eccentricities revealed. One star finds stale chocolate, another finds lost glasses, and one carries a hot water bottle wherever she travels.

Writing about a 2015 online marketing survey of American women’s hand bag use, Lisa Rios observes that the most common items carried were: a wallet, keys, smart phone, and pen, and 15% of those responding to the survey reported carrying a handgun. Her advice to marketers: “Understand her secret self. Handbags are a land of contradiction and comforts.”

What’s inside the maiko’s kago?

Given all this attention to the contents of a woman’s handbag as a window on her life, work, and personality, we have to ask, “What does a maiko typically carry to ozashiki? What do these contents reveal?”

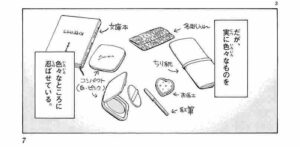

It turns out that maiko may pack all kinds of handy items in the kago.

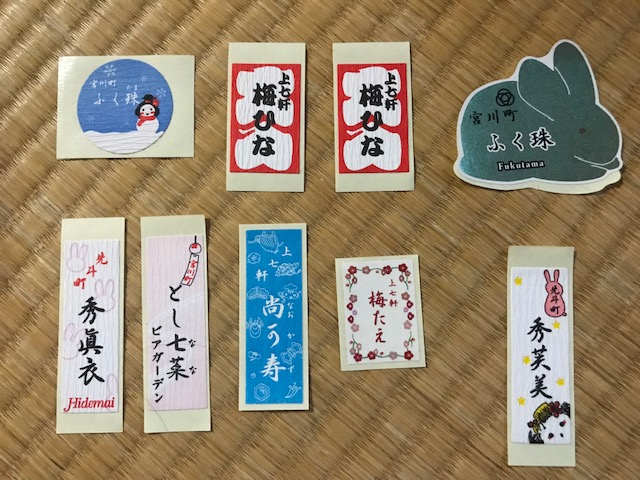

There’s a mix of tradition (maiko cosmetics) and contemporary tools (a cellphone). They may pack fresh tabi socks, a Japanese wrapping cloth (furoshiki), a small notebook, and a small emergency umbrella. Of course, maiko carry a supply of their hanameishi name cards.

What’s inside Momohana’s kago? She has her kuchibeni lip coloring and lip brush. She also packs tissue, hanameishi, and a small paperback book. Hmm, what’s she reading? Too bad we can’t see the title.

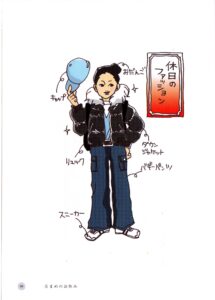

In her 2007 book Maiko Etiquette, Ichimame describes packing a tenugui (cloth towel) for protecting her kimono if she will be dining. She includes cough drops to keep her throat from getting dry over an evening’s hours of conversation (66). On her day off, when Ichimame wears typical teenage street clothes, she takes a backpack and a wallet , as shown below(92).

What’s missing from the maiko’s kago?

Two standout items: keys and a wallet.

Looking at videos and surveys of women’s handbags, you notice almost everyone has a wallet for cash, cards, and personal iterms, and keys to their home and/or car. This reminds us of the maiko’s position. She takes taxis or walks to the teahouse and back to her okiya. People will expect her at both places–no need for keys. The taxi will charge the expense to her okiya.

As an apprentice, she will receive some spending money and she may accept tips, but she does not need money for her engagements or lessons. The lack of money and keys underscores the maiko’s innocence and dependence. It also avoids associating the maiko with materialism.

The “Bad Girls” handbag tells a different story

In contrast, as Sharon Kinsella observes, reporters hoping for scandalous stories about kogals (kogyaru) would ask them to dump the contents of their purses for the camera. “Reporters looked especially for cash, personal organizers, list of phone numbers, brand-name wallets, cell phones, and expensive cosmetic pouches and cosmetics. Merely the appearance of these items…was enough to stimulate ideas about precocious acquisitiveness and prostitution” (88). The reporters’ act aims at policing young women whom the media deems delinquent. Here, fascination with handbag contents becomes especially voyeuristic and sexualized, while both demonizing and exploiting the “bad girl.”

Although kago are expensive, they are associated with Japanese craftsmanship and the preservation of a traditional arts world. And, as the few examples in the literature on maiko show, the kago is filled only with items that allude to the maiko’s attention to her clients and proper maiko deportment. It’s a good girl’s handbag.

Featured Image on Unsplash

Today’s featured image comes from Boudewijn Huysmans. Thanks for posting this on Unsplash.

He reports taking the photo in Gion in fall 2017. The maiko politely stopped for the photo, but only for 15 seconds. Yet, she delighted the photographer with the perfect coordination of her maiko costume. He writes, “Nothing about her appearance was out of tune”. Certainly, her ozashiki kago finishes her maiko look.

REFERENCES

Aihara Kyoko, Kyoto hanamachi fasshon no bi to kokoro [The soul and beauty of Kyoto’s hanamachi fashion]. Tokyo: Tankōsha, 2011.

Davis, Anita. What’s Inside? A Century of Women and Handbags, 1900-1999. Et Alia: Little Rock, AK, 2018.

Kamishichiken Ichimame. Illustrated by Katsuyama Keiko. Maiko etiquette. Tokyo: Daiwa Shobō, 2007.

Kinsella, Sharon. Schoolgirls, Money and Rebellion in Japan. New York : Routledge, 2014.

Koyama Aiko. Maiko-san-chi no Makanai-san. Serialized manga. Episode 75, Volume 8. Shōgakukan, 2018. Cover image is Volume 6, 2018. For its new online anime adaptation, NHK World translates the manga title as Kiyo in Kyoto: From the Maiko House.

Rios, Lisa. “ConneCKtions Research Study: What’s in her handbag?” Cramer-Krasselt, 2021. Online at https://c-k.com/connecktions-research-study-whats-in-her-handbag/ Accessed August 31, 2021.

Jan Bardsley, “What’s inside the maiko’s handbag?” Janbardsley.web.unc.edu. October 15, 2021.

This blog is intended for educational purposes only. I make every effort to cite sources properly.