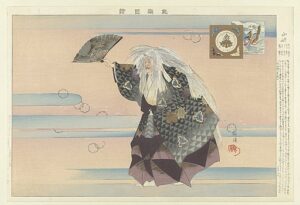

Yamamba, Japan’s legendary mountain witch, always fascinates. She springs to life across cryptic tales, dazzling art, and the majestic Noh theater. I remember how my students enjoyed discussing the yamamba in Japanese literature and theater classes. Was she a cautionary tale? A sign of feminist bravura? How did the meanings of her persona shift with the various tales and performances?

Luckily, a new book co-edited by Rebecca Copeland and Linda C. Ehrlich guides us through these issues and more.

Luckily, a new book co-edited by Rebecca Copeland and Linda C. Ehrlich guides us through these issues and more.

Yamamba: In Search of the Mountain Witch (Stonebridge Press, 2021) takes a fresh, innovative approach. There’s poetry, artwork, short fiction, and interviews with Japanese women who perform Yamamba roles. Japanese literary and folklore scholar Noriko Reider offers an excellent cultural history of the mountain witch to set the stage.

Eager to find out more, I caught up with Copeland (RC) and Ehrlich (LCE) for a yamamba conversation. You can also hear this amazing duo interviewed by Amy Chavez on the Books on Asia podcast.

Who is the yamamba?

JB: Some readers may be learning about the yamamba for the first time. How would you introduce her?

RC: Typically, the yamamba is a mysterious old woman. She lives in the mountains beyond the normalcy of human habitation. She can be fearsome and destructive. But she can also be gentle and supportive. In a way, she is a representation of the awesomeness of nature itself.

JB: An intriguing character for sure. And, as your book shows, she cannot be easily defined or contained.

LCE: True. The yamamba transcends standard definitions of freedom and, conversely, of control. Noriko Mizuta refers to her as “gender-transcendent.” It’s impossible to separate the yamamba’s spirit from the vastness of mountains.

Freeing the Old Woman from Social Constraints

JB: How does the yamamba challenge views of older women even today?

LCE: Good question. Too often, we see the older woman either ignored or feared. This occurs especially in cultures where a multigenerational family is no longer the norm. Various representations of the yamamba put the older woman front and center, and they explore her potential.

RC: I absolutely agree. The old woman gets pushed to the periphery. Society expects her to fade silently into the background. The yamamba may be exiled in the mountains. But she does not relinquish her power. If anything, she uses her role as a social outcaste to mock those who would shun her. Their fear of her only accrues to her power.

At Ease with Aging: To Be Old, Wild, and Free

JB: Speaking of fear, I notice that Japanese art featuring the yamamba tends to show aging as ferocious and frightening. Can we read these images from a feminist perspective?

RC: The yamamba shows how embracing age can be liberating.

During the pandemic lockdown, I think a lot of older women began to discover their latent strength. And we felt freer in our appearance, too. We stopped dyeing our hair and worrying about our clothes. As we spent more and more time in our dark zoom caves, we began to rely increasingly on the power of our own voices.

The yamamba reminds us that it’s okay to be old and wild and free.

After all, people get out of your way when you’re tearing down a mountainside, white hair splayed about you, mouth agape.

Yamamba as Feminist: “The Smile of a Mountain Witch”

LCE: A feminist approach comes across most strongly in Ōba Minako’s story, “Smile of a Mountain Witch.” It was a stroke of good luck to get permission to include the full English translation by Noriko Mizuta in our volume. Actually, it was this story that drew Rebecca and me, separately, to this topic.

RC: Ōba’s story is a bold reimagining, and reclaiming, of the yamamba myth in modern times. She brilliantly captures the yamamba’s poignant mix of nurturing, inner strength and isolation. And the story intimates that the witch’s social position and her mind-reading ability may link modern mothers and daughters.

JB: An evocative story. I also enjoy the new stories, poetry, and artwork that you include.

RC: Linda and I wanted to show multiplicity of the yamamba. She enchants, terrifies, and at times, even comforts. Including creative responses in different formats helped us accomplish this.

The Yamamba Inspires Creative Responses

LCE: Right. We tried hard to incorporate a variety of writing styles and tones, and a wide range of approaches to the yamamba. We wanted to include contributions from practicing artists as well as scholar-artists.

LCE: We explored Yamamba through classical theatre, experimental theatre, the visual arts, literature—in her awe-inspiring aspects and in her grotesque aspects. Several of the contributors brought the yamamba story up to contemporary times.

RC: For example, David Holloway’s enigmatic short story captures her horrific side. On the other hand, my story, set in the North Carolina mountains, plays on this fear but also draws on Yamamba’s maternal nature and wisdom.

“Yamamba Shrine Box”

“Yamamba Shrine Box.” Dr. Laura Miller.

Ei’ichi Shibusawa-Seigo Arai Endowed Professor in Japanese Studies and Professor of History, University of Missouri St. Louis. 2021.

RC: Laura Miller’s essay about her creation of the retablo, which she terms a shrine box, gives yet a different picture. She emphasizes the yamamba’s playfulness and irreverence. She also introduces those naughty ganguro girls with their dark tans, silver hair and yamamba swagger.

Yamamba Poetry and Performance

JB: I like the way poetry in the volume pushes the reader to imagine the character’s motivations. We sense her grandeur. Linda’s lyrical poem, along with the imagistic poems by Noriko Mizuta convey the awesomeness of the yamamba and her association with nature.

JB: I also liked your book’s inclusion of women who bring the yamamba to life on stage. There’s Ann Sherif’s interview with Noh actors Uzawa Hisa and Uzawa Hikaru and Rebecca’s interview with avant-garde choreographer Yokoshi Yasuko. You explore the yamamba from many angles.

Seeking the Yamamba

LCE: We entitle our introduction to the book “Beyond Place, Before Time—Why We Seek the Yamamba.” And indeed the sense of “seeking” is present on every page. In that sense, our book offers the excitement of exploration of an elusive figure. We’re not trying to “capture” the yamamba (an impossible task) but rather to celebrate her.

LCE: We entitle our introduction to the book “Beyond Place, Before Time—Why We Seek the Yamamba.” And indeed the sense of “seeking” is present on every page. In that sense, our book offers the excitement of exploration of an elusive figure. We’re not trying to “capture” the yamamba (an impossible task) but rather to celebrate her.

JB: That sense of “seeking” certainly does come through in every contribution. You make it clear that the yamamba cannot be captured, but she can be contemplated, celebrated, performed, and even emulated.

Congratulations on your innovative book, Rebecca and Linda. You’re bringing yamamba power to new readers across the world.

We would like to thank Katie Stephens, PhD student in Japanese literature at Washington University, who participated in a live conversation with Rebecca Copeland about Yamamba hosted by University of Missouri, St. Louis. The April 2021 event was sponsored by the Ei’ichi Shibusawa-Seigo Arai Endowed Professorship in Japanese Studies and UMSL Global. Katie’s enthusiasm for the book has inspired further conversations.

Jan Bardsley, “Yamamba: In Search of Japan’s Mountain Witch.” janbardsley. web.unc.edu July 29, 2021.