The two maiko catch sight of Momohana walking purposefully. Where is she going? It’s their afternoon free time between lessons and evening parties. “I bet she’s making afternoon greetings at the teahouses,” says one. “What a serious girl.” Impressed, the two maiko resolve to make more effort themselves. This scene in Koyama Aiko’s maiko manga introduces the “afternoon greeting.”

A maiko’s afternoon greetings: What’s the purpose? How may we learn from the practice?

Today’s post takes us to the custom of ochaya mawari, that is, “making the rounds of the teahouses.” What’s the purpose of this practice? What can it tell us about the importance of even brief face-to-face communication?

The maiko must develop good relations with teahouse managers

Maiko and geiko depend on invitations to participate in ozashiki (evening teahouse parties). That makes it important to stay on good terms with all the women who manage teahouses in their hanamachi (geisha neighborhood). Making the rounds of teahouses during free time in the afternoon offers one way to do this. As a new member of the hanamachi, the maiko must get her face known in the neighborhood. Ochaya-mawari presents a time-honored way to make a good impression.

Artist Koyama explains the custom

Kiyo in Kyoto: From the Maiko House [Maiko-san-chi no Makanai-san], manga by Koyama Aiko. Episode 32, Volume 4. Shōgakukan, 2017.

In her manga series Kiyo in Kyoto: From the Maiko House, Koyama Aiko introduces many hanamachi customs. Momohana, her star maiko, has remarkable talent. But she also works tirelessly to become the best maiko that she can be. Naturally, she leads the others in taking her afternoon greetings seriously.

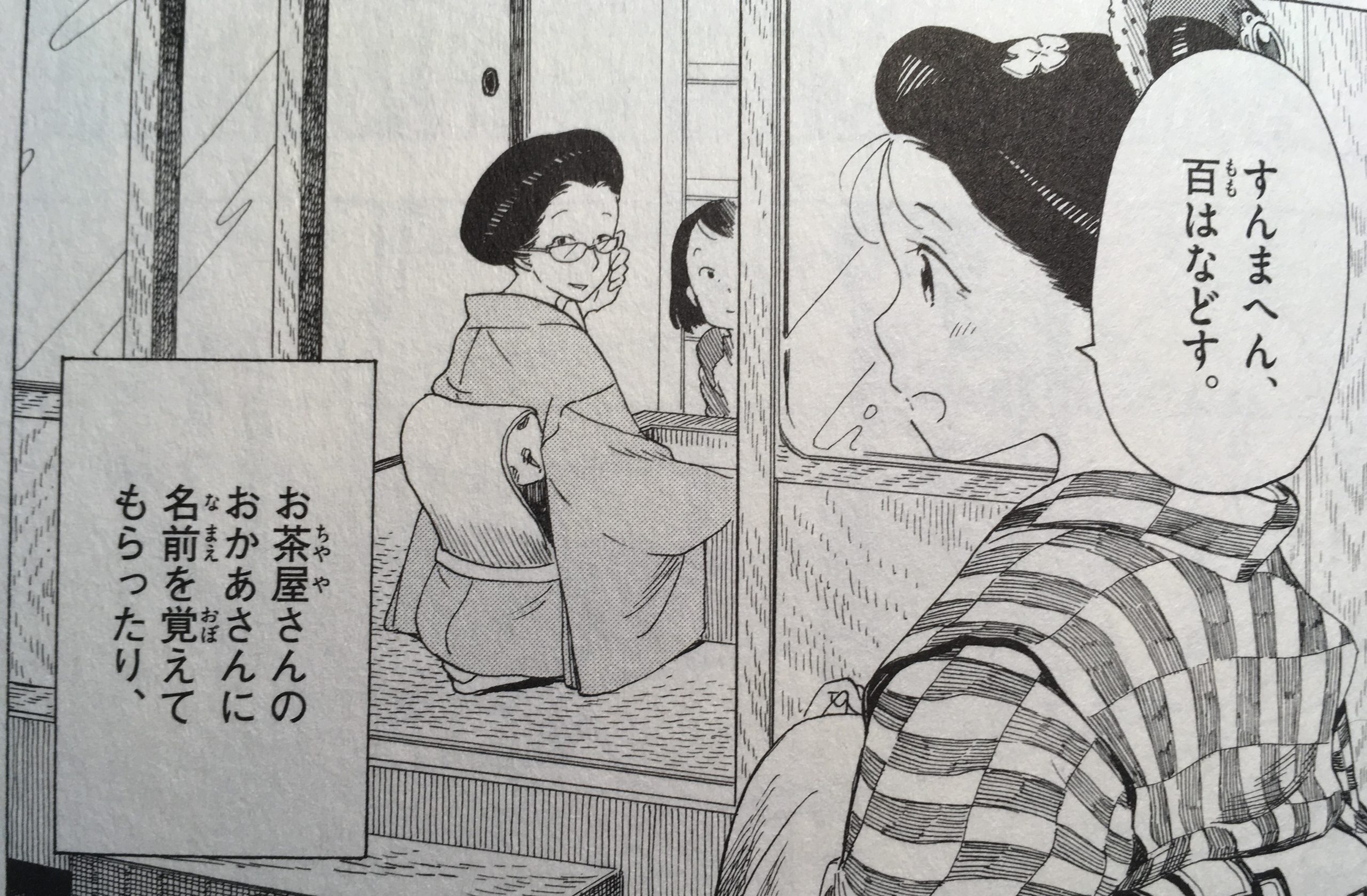

Momohana greets the teahouse mother. Maiko-san-chi no Makanai-san, manga by Koyama Aiko. Episode 32, Volume 4. Shōgakukan, 2017.

As Momohana’s example illustrates, the courtesy call is a quick greeting. She slides open the door to the genkan (entryway). This is a space viewed as in-between the public and private. Next, Momohana calls out in the hanamachi dialect, “Excuse me, it’s Momohana.” (すんまへん、百はなどす。Sunmahen, Momohana dosu). She mentions that her schedule is open at 8pm, so she would be free to attend an ozashiki at this teahouse.

The smile on the okami-san’s (manager’s) face shows that Momohana is making a good impression indeed. Of course, that Momohana earns praise for making the rounds implies that she is an unusually dutiful maiko.

Afternoon greetings as a staple of maiko life

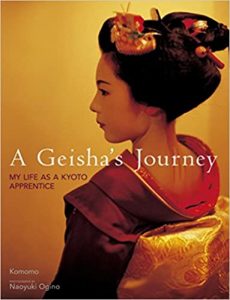

We find the importance of the maiko’s “afternoon rounds” emphasized in many books on hanamachi life. In A Geisha’s Journey (2008), Komomo describes how, as a maiko, she made lunchtime “visits to each of the almost forty tea houses in Miyagawa-chō, where many of the ozashiki (evening parties) were held. Believe or not, I did this every day for two whole years, just to drum up business for our okiya” (32).

Writing about hanamachi life in the 1960s and 1970s, Mineko Iwasaki notes even “geiko had to pay their courtesy calls in the afternoon, in order to remain on good terms with the owners of the ochaya and the senior maiko and geiko. If any member of the community was sick or injured, protocol demanded that they call on her promptly to voice their concern” (79-80).

Face-to-face communication: A useful skill beyond the hanamachi

Even in our digital age, experts in organizational relations promote in-person communication. In “The Lost Art of Face to Face Communication and Why it’s still important,” The Lee Group champions the practice for several reasons. Meeting people in person can communicate through body language, help build relationships, and foster collaboration. It also allows for better discussion of sensitive issues. One may pick up cues in person that get missed in email.

We also understand that meeting in person takes extra effort and time. This shows a friendly respect in ways that texts and emails cannot.

Isolated from the usual face-to-face encounters during the pandemic, I missed casual human interactions. Whether pleasant, irritating, or comic, they added stimulation to my day. Now that it’s easier to go out again–still masked, safely distant–I will embrace the maiko’s practice of getting out to greet shopkeepers and passersby in my neighborhood. Learning from the hanamachi, I realize this practice builds community.

References

Iwasaki Mineko and Rande Brown. Geisha, a Life. Translated by Rande Brown. New York: Atria, 2002.

Komomo and Naoyuki Ogino. A Geisha’s Journey: My Life as a Kyoto Apprentice. Translated by Gearoid Reidy and Philip Price. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 2008.

Koyama Aiko. Maiko-san-chi no Makanai-san. Serialized manga. Episode 32, Volume 4. Shōgakukan, 2017. For its new online anime adaptation, NHK World translates the manga title as Kiyo in Kyoto: From the Maiko House.

Jan Bardsley, “How a Star Maiko Makes a Good Impression: Afternoon Greetings,” janbardsley.web.unc.edu, April 15, 2021.