The friendly sight of clothes hanging on the line

“Seeing laundry hanging outside on the line.” The young Japanese student responded with a smile. We were talking about signs of home and comfort. Studying in the U.S., he missed this common sight of everyday life in his neighborhood in Japan. Scenes like this one captured in the photo below of an Osaka home convey hominess to many Japanese.

I confess that when I first came to Tokyo in 1971, the sight of clothes hanging outside tall apartment buildings startled me. Growing up in a small suburb in southern California, I had become accustomed to dryers. Clotheslines were something from my childhood in the 1950s. Laundry was pretty invisible.

But, when we lived in Tokyo in 2018-19, we regularly hung wash out to dry on the small veranda outside our first-floor apartment. A large green hedge hid all but the tops of it. As you walked by our several-story building, you could see lots of laundry wafting in the breeze on the verandas. Helpfully, the morning weather report advised whether the day looked good for drying the wash outside.

What about laundry customs in Kyoto’s geisha neighborhoods (hanamachi)? As we explore in this post, evidence of this ordinary chore remains out of sight in these refined neighborhoods. Little wonder that this invisibility gives way to stories about hidden spaces and confessions of washing machine mishaps. All these accounts turn our attention to the difference between the front and back stages of the hanamachi.

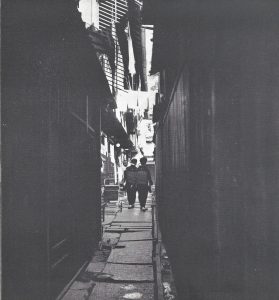

Laundry in everyday Pontochō, 1954

“Washing is hung out over one of the [alleys] of Pontochō.” Perkins, Percival Densmore. Geisha of Pontocho. Photos. Tokyo News Service, 1954.

Hanging clothes on the okiya’s hidden veranda today

Today, the teahouses and okiya of Kyoto’s hanamachi still convey a quiet, elegant charm, like this Gion dwelling photographed here. So, where does the laundry hang?

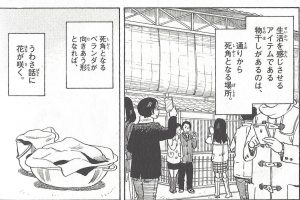

Aiko Koyama’s manga Kiyo in Kyoto gives her readers a look behind the scenes. She takes us past the task of doing the wash to the aesthetics of the hanamachi and its hidden conversations.

Trainee Riko on the okiya veranda. Maiko-san-chi-no Makanai-san, 2017. Koyama Aiko. Vol. 6, Epi. 59,p. 78.

Here, we see shikomi trainee Riko hanging up laundry on her okiya veranda. She gazes at other, nearly adjacent okiya verandas. She sees the okiya helpers hanging the laundry, too. Riko overhears them talking excitedly about a new maiko. The hidden verandas make an excellent space for gossip.

In the next frame, the narrator explains how the neighborhood preserves its elegant façade by hanging laundry on these verandas behind the buildings.

We see tourists eager to pose for photos in front of the beautiful okiya. Hiding the laundry keeps evidence of ordinary, everyday life at bay. This frame also makes the point that the hanamachi does not aim to convey hominess, but the air of a world apart.

A private space for confidential chats

Twins Nozomi (maiko Yumehana) and Megumi. https://www.pref.shimane.lg.jp/admin/seisaku/koho/photo/172/4.html

The hidden veranda creates a private space, too, for the maiko Yumehana in NHK-TV drama Dandan (2008-09). She retreats to the veranda for more than hanging laundry. This is a space for secret phone calls, for private chats with her twin sister, and to reflect on her future. Notably, we never see the dignified matriarch of this okiya/teahouse on the veranda. She does not do housework.

The would-be maiko learns laundry skills

Moving from the veranda to the space of the washing machine takes us to the humorous confessions of a shikomi trainee. Her name is Maiko, though written with different characters than “apprentice geisha.” The “baby of her family” and the last of five sisters, Maiko knew nothing about housework until coming to the okiya.

Moving from the veranda to the space of the washing machine takes us to the humorous confessions of a shikomi trainee. Her name is Maiko, though written with different characters than “apprentice geisha.” The “baby of her family” and the last of five sisters, Maiko knew nothing about housework until coming to the okiya.

Maiko describes how doing chores around the okiya can challenge the brand new shikomi. She explains how the trainee assists her elder geiko and maiko sisters with their kimono, runs errands for her mother, and often helps with cleaning.

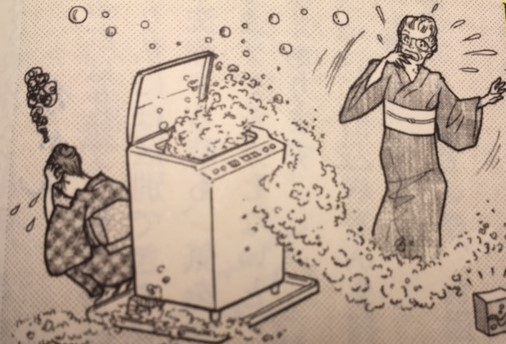

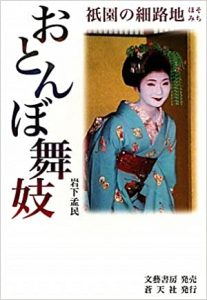

A bad laundry day for the trainee. Iwashita Takehito, Gion no hosomichi: Otonbo maiko [The narrow road to Gion: The youngest child becomes a maiko] (Tokyo: Bungei Shobō, 2009), 54.

Maiko was new to washing machines. She also didn’t know how to separate colors, once turning everything pink by mixing red and white things together. Nor did she know how to separate different articles by their material. This comic shows how Maiko learned the hard way: Too much soap led to bubbles bursting out the machine. (Exaggerated here for comic effect).

Luckily, Maiko seems to have learned laundry skills well by the time she debuted as a maiko. But, at this point, she turned her attention full-time to maiko arts lessons, teahouse parties, and Kyoto booster events. No more need to think about washing machines!

The laundry space in maiko stories

As we see, maiko stories highlight the okiya laundry space as a site of ordinary life, hijinks, and high drama–all unseen from the street. The mystique of the hanamachi façade piques curiosity about what happens within the refined dwellings, giving rise to all kinds of stories of backstage life.

Having finished this post, I can go hang the laundry outside on a sunny day in North Carolina. Feels pretty homey here, too.

References

Iwashita Takehito. Gion no hosomichi: Otonbo maiko [The narrow road to Gion: The youngest child becomes a maiko] Tokyo: Bungei Shobō, 2009, 54.

Koyama Aiko. Maiko-san-chi no Makanai-san. Serialized manga. Volume 6. Episode 59. Shōgakukan, 2017. For its new online anime adaptation, NHK World translates the manga title as Kiyo in Kyoto: From the Maiko House.

Perkins, Percival Densmore. Photographs by Francis Haar. Geisha of Pontocho. Tokyo News Service, 1954.

Jan Bardsley, “Maiko Stories: Hidden Laundry Spaces,” janbardsley.web.unc.edu, May 19, 2021.