Chapter scope: This chapter asks how representations of the maiko have shifted from “victim to artist” in popular narratives produced since the 1950s. It examines two acclaimed films from the 1950s, a serialized drama broadcast on national TV, and two bestselling narrative manga crafted to appeal to girls and women. The chapter invites readers to consider these narratives against changing cultural landscapes.

This page includes reading questions, discussion activities, and short writing

exercises.

Reading Questions:

Keep these questions in mind as you read the chapter and organize your thoughts.

Introduction to chapter:

What is the main argument of this chapter?

What kinds of questions and sources does the author cite?

[Post-reading] Did the chapter accomplish its aims? Identify strengths and weaknesses of the method and argument.

Gion bayashi (A Geisha), 1953 film, Mizoguchi Kenji, director

- What do you learn about Mizoguchi and his involvement with the karyūkai (world of geisha) as a filmmaker?

- How does his 1937 film, Gion no shimai (Sisters of the Gion) represent the lives of geiko in that era? *Many libraries have DVD copies of this film. It is available through Criterion Collection.

- How does Mizoguchi link the maiko to Japanese national identity through the speech of the maiko’s teacher (114-15)?

- How does Eiko learn about expectations for the maiko through her conversations with her teacher about the new Constitution (117)?

- What does Eiko learn about danna from another maiko in her cohort (118)?

- What societal issues shape the background for Gion bayashi?

- How does Gion bayashi depict the status of the maiko and geiko in 1953?

Janken musume, 1955 musical film, Sugie Toshio, director

- What problem does the maiko Hinagiku face and how is it resolved?

- Like Eiko in Gion bayashi, the young leads in Janken musume represent “the postwar teenager.” How do these films characterize this new generation?

- What do we learn about expectations for maiko in Yumi’s conversation with her elders (121-22)?

- How does young Saitō trick his father, and what do we learn about the Saitō Family Code?

- How does the interaction between Ruri’s high school teacher, Kamezawa Sensei, and Ruri’s mother shape the film’s attitude toward the world of geisha (122-23)?

- How would global audiences react today to a comedy depicting a young woman in jeopardy? Can you think of any other films, past or present, that work with this theme?

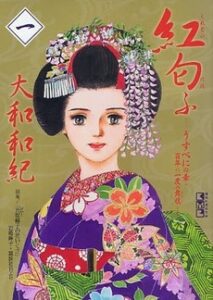

Kurenai niou (Crimson Fragrance), 2003-07 narrative manga, Yamato Waki, artist

*Note: Some of Yamato’s other works are available in English translation: Tale of Genji (Kodansha Bilingual Comics); Haikara-san: Here Comes Miss Modern (Tōei DVD).

- Who is Iwasaki Mineko and how does Yamato’s manga adapt her autobiography?

- What techniques and messages characterize Yamato’s work?

- How does Yamato express maiko Sakuya’s sense of a division between her public role as a maiko and her “real self” (127-28)?

- How does Sakuya respond to the harassment of clients and geiko?

- Looking closely at frames from the manga on p. 129, consider how Yamato communicates the dynamics of the scene and Sakuya standing up for herself. How would you compare this to the Gion bayashi frame of Eiko, p. 115?

- We encountered the terms “Fujiyama” and “geisha girls” in Gion bayashi. How does Yamato use them to characterize attitudes of international visitors in Japan toward maiko/geiko ?

- How does the fight between Sakuya and Gion gatekeepers near the end of the manga show division over expectations for maiko and geiko? What seems to be the cause of this division?

- Although Kurenai niou is set in the 1960s-1970s, it was produced in the 2000s. What messages about work, romance, and sexuality does it communicate?

Dandan, 2008-09 NHK-TV morning drama, Aoki Shin’ya, producer

- How does this drama bring together families of two different geographical locales in Japan?

- How does maiko Nozomi’s rural grandmother learn to appreciate the arts of the Gion geiko?

- How does Dandan characterize the way the Gion–teahouse leaders, geiko, and clients– nurtures the maiko?

- How does Dandan elevate the maiko’s artistic skill and position as representative of Gion in Nozomi’s fateful encounter with a music producer (133)?

- How does Dandan reassure viewers about the future of Japan?

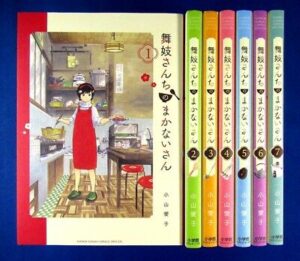

Maiko-san-chi no Makanai-san (Miss Cook for the Maiko Girls), girls comic serialized since 2016, Koyama Aiko, artist

*Note: NHK-World began broadcasting an anime version in 2021 as Kiyo in Kyoto ashttps://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/maikosan/ You can find many frames from the manga online.

- How does this manga characterize the maiko’s world backstage at the okiya?

- Looking closely at the cover image on p. 136, what expectations do you have for this manga?

- What role do teenage appetites and home cooking play in these stories? How do they affect the performance of “maiko likeness.”

- The lead maiko, Sumire/Momohana, epitomizes the maiko-like maiko. Identify the traits that win her this praise.

- How does Koyama’s manga characterize the lone geiko in the story? What do we learn about her?

- How would you contrast the ozashiki parties and clients in this manga with those in the 1950s films and Yamato’s manga?

- How does the athletic maiko Riko bring a different view to this world and earn a scolding (137)?

Conclusion to chapter:

What arguments does Bardsley make in the Conclusion?

What comparisons among these narratives stand out as important to you?

What other issues or comparisons do you see that Bardsley does not mention?

CLASS DISCUSSION

Broad Chapter Discussion Questions: How do these narratives respond to the concerns of their eras? How do changing representations of danna (patrons) and the atmosphere of ozashiki parties contribute to re-imagining the maiko’s role? How do these narratives differently frame geisha/geiko? What do we learn about the concept of “maiko likeness” at the heart of Maiko Masquerade?

Class/Group Discussion Activity (45 minutes)

- Initial class work: Instructor leads the class in identifying five issues useful to discussing the movies and manga in the chapter. Put these on the board. For example, you might ask, “How do the movies/manga characterize geiko/geisha?” [Discussion will produce various answers such as poor; wealthy; graceful; athletic; loyal, etc., depending on the text].

- Small group discussion: Students divide into five groups; each group takes one of the movie/manga to discuss. Each lists specific points from their text that relate to the five issues.

- Presentation: Each group presents its list to the class. The group may want to raise new issues, too. What are your overall findings/

- Wrap-up: Discuss how your findings relate to the themes of your class.

Short Writing Assignments:

Your school is hosting a Japanese film festival and wants film suggestions.

Make a case for adding Gion bayashi or Janken musume to the festival. Briefly describe the film, argue what it brings to the festival. [You decide what the theme and goals of the festival are. Tailor your proposal to fit those]. (250 words)

You learn that a publisher wants suggestions for a Japanese manga to publish in translation. Make the case for either Kurenai niou or Maiko-san-chi no Makanai-san. Why should your choice be made available in translation? (250 words)

Suggestions for Further Reading

Alisa Freedman. “Romance of the Taishō Schoolgirl in Shōjo Manga: Here Comes Miss Modern.” In Shōjo across Media: Exploring “Girl” Practices in Contemporary Japan, edited by Jaqueline Berndt, Kazumi Nagaike, Fusami Ogi, 25–48. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

Keiko I. McDonald. Reading a Japanese Film: Cinema in Context. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2006.

Jennifer S. Prough. Straight from the Heart: Gender, Intimacy, and the Cultural Production of Shōjo Manga. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2011.

Catherine Russell. Classical Japanese Cinema Revisited. London: Bloomsbury, 2011.

Deborah Shamoon. Passionate Friendship: The Aesthetics of Girls’ Culture in Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2012.