Chapter 5. Adventures of a Boy Maiko: There Goes Chiyogiku!

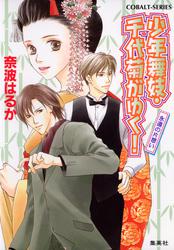

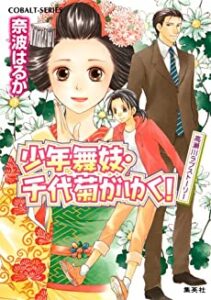

Boy Maiko: There Goes Chiyogiku!Author Nanami Haruka. vol. 43., Takase River love story]. Illustrator Hori Erio.

Shūeisha. Copyright ©2012.

Chapter Scope: This chapter explores gender masquerades in the popular 2002-14 light-fiction series, Shōnen maiko: Chiyogiku ga yuku! (Boy maiko: There goes Chiyogiku!) by Nanami Haruka. After considering the light-fiction genre and BL conventions, we turn to questions about the characters, spaces, and themes in Chiyogiku.

Try reading the original: Students in third- or fourth-year Japanese will find Chiyogiku readable. Author Nanami Haruka provides furigana to make kanji-reading accessible. It’s easy and inexpensive to order volumes online.

Reading & Discussion Questions:

- Characterize the light-fiction genre (raito noberu): Describe its target audience, cover art, ease of reading, use of Afterword (atogaki), and its effect on the publishing industry and literary studies.

- How does the light-fiction genre employ cross-dressed characters?

- Search for Chiyogiku covers online. How do they shape your expectations for the reading experience? Try searching “images” with the Japanese series title: 少年舞妓:千代菊が行く

- What is the Chiyogiku series about and how did the boy Mikiya begin his maiko masquerade? What kinds of adventures ensue? How does the series end?

- How does sexual play and harassment figure in Chiyogiku plots? Bardsley compares this with similar scenes in My Geisha, an American comic film. What fiction, manga, or film would you use for comparing Chiyogiku?

- How does Mikiya feel about his maiko masquerade?

- How would you compare the settings in the Chiyogiku series with what you have learned about the hanamachi as a historic locale, tourist space, and residential neighborhood?

- An onnagata (Kabuki female role player) tells Chiyogiku, “You perform the ‘imagined woman.’ You embody the ‘idealized image of woman’ that a flesh-and-blood woman cannot (154).” What does this comment reveal about gendered performance in modern Kabuki?

- What “technologies of gender” (language, costume, etc.) does Mikiya employ to create Chiyogiku? What distinguishes his boy self from Chiyogiku?

- How does host Shion cross gender to create the perfect host? What does Shion’s performance say about “salon masculinity” in the Chiyogiku series?

- Chiyogiku/Mikiya moves easily between two gendered persona. How does the series both subvert and reinforce gender norms?

- How would you compare Chiyogiku’s maiko masquerade to other examples in the book such as the teenagers in Koyama Aiko’s cooking manga (ch.4) or the autobiographical writing of maiko Ichimame (ch. 3)?

Suggestions for Further Viewing and Reading

Your Name :君の名はKimi no na wa, 2016 animated film directed by Shinkai Makoto. This award-winning, globally popular film imagines two high school students, a girl and boy, suddenly and inexplicably changing bodies. According to Wikipedia, Shinkai published the story in light-fiction form one month before the film’s debut. How would you compare crossing gender in this film and the Chiyogiku series?

Kabuki & Takazaruka Revue Cross-Gender Roles

Deborah Shamoon, “Revolutionary Romance: The Rose of Versailles and the Transformation of Shōjo Manga.” Mechademia 2: Networks of Desire (2007): 3-17.

Maki Isaka, Ch. 7, “Female Onnagata in the Porous Labyrinth,” pp. 112-138 in Maki Isaka, Onnagata: A Labyrinth of Gendering in Kabuki Theater (University of Washington Press, 2016).

Medieval Narratives in Japan:

Rosette F. Willig. The Changelings: A Classical Japanese Court Tale. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1983. Himuro Saeko adapted this medieval tale of cross-gender identities in her 1983 novel, Za chenji [The change], which Hiromi Tsuchiya Dollase discusses in Age of Shōjo (SUNY Press, 2019).

Sachi Schmidt-Hori explores love stories of chigo (acolytes) in Tales of Idolized Boys: Male-Male Love in Medieval Japanese Buddhist Narratives (Univ. of Hawai’i Press, 2021).

For more on BL (Boys Love) Genres, see:

McLelland, Mark J., Kazumi Nagaike, Katsuhiko Suganuma, and James Welker, eds. Boys Love Manga and Beyond: History, Culture, and Community in Japan. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2015.