There goes a maiko, carrying her trademark umbrella. It’s called janomegasa 蛇の目傘, the “snake’s eye umbrella.” A slender handcrafted oiled-paper-and-bamboo umbrella. Like other elements of hanamachi fashion, it conveys respect for Kyoto craftsmanship. On sunny days, we see maiko carrying a parasol. Crafted from paper or fabric, these parasols — higasa日傘 — are not waterproof.

Today’s post follows the maiko’s umbrella and parasol into a different world, trainee mistakes, and even geiko headaches. What stories do they tell?

*For more on the history and crafting of these Japanese umbrellas, see the websites listed at the end of this post.

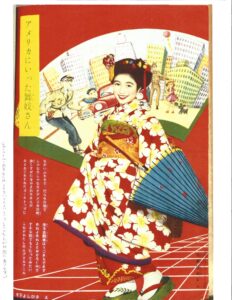

Janomegasa as Invitation to Maiko Play in the 2000s

Bright red janomegasa often appear in the opening credits to maiko movies.

Moving with the music, twirling red umbrellas invite movie viewers to a romantic world different from their own. The image above, the program cover for the 2018 live version of musical Lady Maiko, also displays an umbrella collage. Notice these umbrellas have the janome snake’s eye pattern. (Janome has also become the generic term for this slender kind of traditional Japanese umbrella, even if it is all one color).

An accessory to distinguish the maiko from the ordinary girl.

NHK Drama Guide to Dandan. Magazine Mercari. 2022.

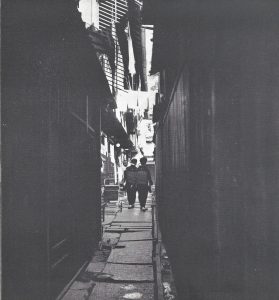

This signature maiko item tells a story. Above, we see the twins starring in the 2008-09 NHK-TV morning drama, Dandan. Megumi, raised as an “ordinary girl,” holds a guitar and wears blue jeans. Clad in kimono, maiko Nozomi carries the handcrafted Kyoto accessory. Right away, we can tell they come from two different worlds.

Maiko Use Janomegasa as Charm Advantage

How do janomegasa play a role in the shikomi trainee’s life?

Former geiko Kiriki Chizu explains.

During her training period, the shikomi must make a good impression on teahouse managers in her hanamachi. She needs them to remember her favorably. She hopes they will call her for teahouse parties once she becomes a maiko.

No wonder Kiriki Chizu sees this positive recognition as “the prime secret to success in Gion” (216). Shikomi must make the most of even a small opportunity to get better known. Even when fetching an umbrella.

For example, on a night when there’s a sudden rain shower, a shikomi may be asked to bring her elder sister’s janomegasa and raincoat to the teahouse. When she arrives, advises Kiriki, the trainee should call out her greetings in a bright, clear voice. Coming to the entrance, the okami-san (manager) will say, “Ah, and your name is? How charming!” And just like that, the shikomi has made a good impression.

One Trainee’s Epic Umbrella Fail

One movie, however, imagines the same teahouse scene going all wrong for the trainee. Lady Maiko (2014), an adaptation of My Fair Lady, shows trainee Haruko learning the hard way about umbrella etiquette.

The Lady Maiko scene opens on a very rainy night. It’s 10:30pm. Haruko gets soaked as she dashes out to bring an umbrella to her elder sister at an evening ozashiki. The geiko is horrified! Haruko has fetched a common plastic umbrella. It’s the cheap, clear kind everyone buys at convenience stores. The geiko sends Haruko right back out in the rain to retrieve the proper one from the okiya.

Tourists’ Vinyl Convenience

For these young women (above), the vinyl umbrella works just fine. But they are not in training to become maiko like Haruko.

Japanology Plus (2015) explains that these plastic umbrellas became widely used in Japan in the 1980s. They account for 60% of the 140 million umbrellas sold yearly in Japan. Although cheap and convenient, they are hard on the environment. While expensive, the bamboo and paper umbrella can last 20 to 30 years with good care.

But let’s get back to Haruko’s umbrella dilemma.

What Umbrella Should Haruko Bring?

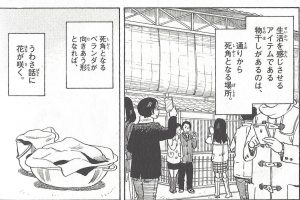

Lady Maiko makes clear that only the old-style Japanese umbrella will do. A later scene depicts three umbrellas opened to dry outside the okiya—two beautiful, richly colored bamboo ones and the offending plastic one.

Cut to the geiko scolding Haruko for failing this basic test of hanamachi culture. For poor Haruko, it’s the last straw. She’s failed at learning the dialect, the maiko arts, and now even basic umbrella etiquette. Despondent, she even loses her voice.

Haruko’s Happy Ending

Luckily for Haruko, by the end of the film, she recovers her voice, masters maiko customs, and wins praise from all. Lady Maiko even features a cheerful umbrella scene that shows Haruko’s new confidence. Breaking into “The Rain in Kyoto Falls Mainly on the Plain,” she even pops open a janomegasa!

Publicity Tool for Lady Maiko

This promotional event (above) for Lady Maiko plays with this signature accessory. The one to the left displays the movie’s title in Japanese. The one to the right reads, “Big hit! Big hit!” For stories about the maiko’s celebratory mokuroku posters behind the cast members, see my April 5, 2021 post

A Geiko’s Umbrella Headache

Geiko Kokimi admires the Gion geiko’s purple janomegasa. Its finely crafted beauty, the look of the washi paper when exposed to the light.

But she ruefully confesses, these precious umbrellas can be a hanamachi headache. One can forget one of these as easily as any other umbrella. When that happens, well, “there goes another 10,000 yen.” (In 2022, these umbrellas cost much more.)

In fact, Kokimi adds with chagrin, she gets nervous every time it looks like rain. She still has not replaced her last expensive janomegasa (48-50).

An Essential Prop in Maiko Stories

Maiko at Nashinoki Shrine Noh Stage, 2018. Wikimedia Commons.Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0

So much more to learn about the janomegasa and higasa parasol as essential props in maiko stories. How did these umbrellas figure in maiko art and photography in the past? Did books on maiko and geisha in English, including images of janomegasa and higasa, stimulate readers abroad to purchase their own Japanese umbrellas? This brief foray into maiko umbrella culture makes me curious to find out more about its early 20th century maiko history.

Next Post: Maiko at the Plum Blossom Festival

The annual Plum Blossom Festival at Kyoto’s Kitano Tenmangū Shrine takes place on February 25th. What’s the story behind this festival? How do maiko and geiko of the Kamishichiken district participate? Our next post explores this popular event.

Learn More about Japanese Umbrellas Online

The websites of Kyoto’s legendary umbrella shops Hiyoshiya and Tsujikura offer excellent guides in English and Japanese. Spectacular photos, too. I also found informative the websites Japan Objects and Tofugu .

A good find! The Japanology Plus series offers an episode on “Umbrellas.” It explains the old and the new, even showing baseball fans cheering on their team with small vinyl umbrellas. It includes an interview with Hiyoshiya manager and umbrella maker, Mr. Kotaro Nishibori, who also invents new forms and uses for the traditional techniques and materials.

FEATURED IMAGE: Janomegasa. Tsujikura website. 2022.

REFERENCES

Japanology Plus. Peter Barakan. Episode Number 46, Season1.

Originally Aired : Thursday, June 18, 2015

Kiriki Chizu. Aisare jōzu ni naru Gion-ryū:Onna migaki [The Gion way to skill in becoming loveable: A woman’s polish]. Tokyo: Kōdansha, 2007.

Suo Masayuki, dir. Maiko wa redī [Lady Maiko]. Tokyo: Toho, 2014.

Yamaguchi Kimijo. Suppin geiko: Kyoto Gion no ukkari nikki [Bare-faced

geiko: My haphazard diary of Gion, Kyoto]. Tokyo: LOCUS, 2007

Jan Bardsley, “The Maiko’s Paper Umbrella,” Janbardsley.web.unc.edu. February 18, 2022.