This is not a psychiatric hospital.

Stop acting like madwomen.

Bored, the Kyoto geiko couldn’t resist boisterous antics. Their famous manners gave way to mischief.

Stuck in a Tokyo hospital recuperating after minor surgery to repair their bald patches, Iwasaki Mineko and her three geiko companions got restless. After all, “it was springtime and we were frisky” (Iwasaki and Brown, 257). Trying to cheer them up, their Tokyo clients sent fine dishes from local restaurants.

But the geiko sneaked out to shop, going out on the town at night “even in our bandages” (257). When they line-danced to the local gas station one afternoon, the head nurse lost her temper. “This is not a psychiatric hospital. Stop acting like madwomen” (257).

The sight of four geiko dancing a conga line on a Tokyo street would make a delightful manga. One of the funniest stories in Iwasaki Mineko’s Geisha, A Life, the incident begs the question, “How did these geiko develop bald spots in the first place?”

What does the maiko bald spot mean?

In today’s blogpost, we explore the maiko’s bald spot. We learn how it can mark both pride and shame, and why present-day maiko are unlikely to develop the patch. Returning to Iwasaki Mineko’s memoir, we see how the patch emphasized her lack of control over her career in 1970.

A patch the size of a five-yen coin

Specially trained hairdressers form the maiko’s elaborate Edo-era hairstyle from the girl’s own shoulder-length hair. She must take care to keep the style in place for 7-10 days.

Liza Dalby explains how “pulling tight a small bundle of hair for the basis of the maiko’s hairstyle” causes a small section of the hair to fall out (45-46). It never grows back. Lesley Downer describes the mark as a “perfectly round little bald patch on the crown” of the maiko’s head (115).

The maiko’s bald spot is the same size as a 5-yen coin. Roughly equivalent to the size of a nickel in the U.S., the coin is small, only 22 mm in diameter (about 3/4 of an inch). Pronounced go en (5 yen), the coin carries the meaning of “good fortune,” also pronounced go en. This makes it a popular coin offering at Shinto shrines. Similarly, some former maiko view their bald spot positively.

The maiko’s bald patch as “medal of honor”

Liza Dalby recalls how one teahouse manager referred to the spot as “the maiko’s medal of honor” — “a mark of the hardships of the training she undertook” (45-46). Since today’s maiko undergo a short apprenticeship, many debuting at 17, “their scalps are probably safe” (46). To many elders in the community, as Dalby explains, the lack of a bald spot speaks to maiko training losing the strict discipline of old. She writes, “from the point of view of most modern Japanese the discipline of the maiko and the geisha is still redoubtable” (46).

Embarrassment at a Tokyo hair salon

“It felt like a slap in the face.”

But not all in Japan interpret evidence of a maiko past positively. As I discuss in Maiko Masquerade, maiko have been stigmatized, especially in 1950s films, as women of the “water trade,” the realm of nightlife entertainment understood to involve sex work. Tokyo stylists, as we see below, sometimes mistook the patch for scalp disease or the mark of an old-fashioned, unstylish woman.

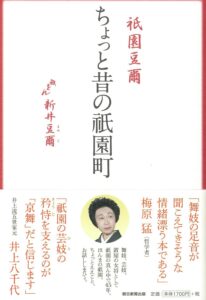

Former Gion geiko Arai Mameji, who debuted as a maiko in 1969, writes about her elder sisters running into trouble when having their hair done in Tokyo.

Arai Mameji. 2015. Gion Mameji: Chotto mukashi no Gion machi

(Mameji of the Gion: The Gion of Recent Past).

Tokyo: Asahi Shimbun Publications, Inc.

One stylist took the bald patch as a sign of a skin illness. She rushed to get another brush so she wouldn’t contaminate the ones the salon usually used, mortifying the former maiko.

Once Arai, too, knocked herself out trying to dress in high fashion, complete with high heels, to visit a Tokyo salon. To avoid the same alarm her elder sisters had caused, Arai mumbled to the stylist that she had a bald patch since she’d been a maiko and wore the elaborate hairstyle of the apprentice. Whatever the reason, the stylist reacted impatiently.

She “shut me up, blurting, ‘You were a maiko, right’, acting as though she couldn’t be bothered with such triviality when she was so busy. It felt like a slap in the face.” The exchange left Arai disheartened. “I felt very disappointed, realizing I am “countrified” after all” (Arai, 60).

“Expo Baldies”: Iwasaki Mineko’s concern

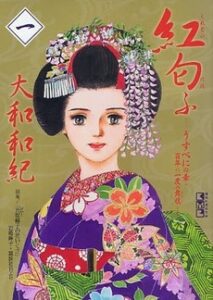

In Crimson Fragrance, artist Yamato Waki’s famous manga adaptation of Iwasaki’s memoir, discovery of the bald patch alarms maiko Sakuya (the Iwasaki character).

Having been a maiko since 1965 and wearing her hairstyle for long periods of time, Sakuya has a bald patch forming. This makes her plead to “turn the collar” to become a geiko. Since geiko wear wigs when in formal costume, Sakuya would no longer worry about her scalp. But Sakuya is refused.

Japan’s 1970 World Exposition (Osaka Expo ’70) was coming up. “The powers that be” requested Gion to have many maiko on hand to perform in the Japanese pavilion to show the traditional arts (Iwasaki and Brown, 207). Thus, the men in charge of Gion ordered maiko to postpone their transition to geiko until after Expo.

Yamato’s manga shows Sakuya’s frustration. She cannot gain any sympathy from the men over her fears about baldness. As an heir to an okiya, Sakuya cannot quit Gion easily either.

As a result of their lengthy apprenticeship, “all of us maiko got the bald patch.” We were teased as “Expo baldies” (Banpaku hage) (vol. 3, 12).

The Maiko Bald Patch Repair Party

In Geisha, A Life, Iwasaki describes the surgery to close her maiko bald patch. “The operation consisted of snipping the bald skin and pulling the edges together to tighten it, similar to a facelift. My incision was closed with twelve teensy stitches” (256-57).

It’s hard to imagine why such a small surgery meant staying for days in the hospital. But it sounds like Iwasaki and her geiko friends knew how to make the most of it.

Our own vocational bodies?

Reading about the maiko’s bald patch makes me wonder about how all of us wear our life experiences on our bodies to some degree. I see the small scars on my face left from chicken pox and a minor fall as a child. But what about signs of my work? In my case, a very loud voice from years as a teacher. For that, I am not sure there is any repair.

I’d like to thank my friend Aki Hirota for help understanding Arai Mameji’s account of bald spot mishaps.

References

Arai Mameji. Gion Mameji: Chotto mukashi no Gion machi [Mameji of the Gion: The

Gion of recent past]. Tokyo: Asahi Shimbun Publications, 2015

Dalby, Liza. Geisha. Berkeley: University of California Press,1983, 2008.

Downer, Lesley. Women of the Pleasure Quarters: The Secret History of the Geisha. New York: Broadway, 2001.

Iwasaki Mineko and Rande Brown. Geisha, a Life. Translated by Rande Brown. New York: Atria, 2002.

Yamato Waki and Iwasaki Mineko. Kurenai niou [Crimson fragrance]. Serialized manga. 2003–07, rpt Tokyo: Kōdansha, 2009.

Jan Bardsley, “The Maiko’s Bald Spot and Repair Party,” janbardsley.web.unc.edu, April 8, 2021.