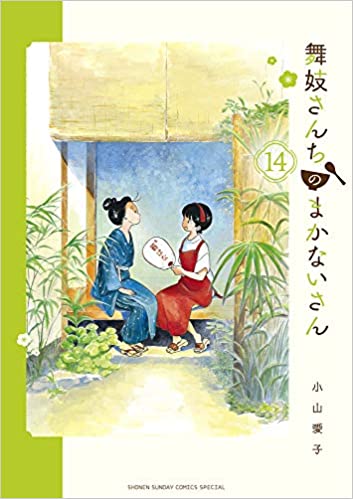

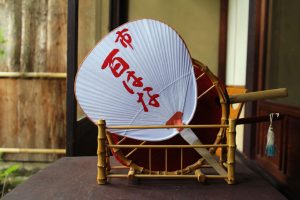

What is the story behind the maiko’s uchiwa fan?

This pretty book-cover image shows a lovely way to stay cool in Kyoto’s summer months. Here, we see maiko Momohana lifting her chin to catch the breeze as her best friend Kiyo waves the fan. The fan bears the maiko Momohana’s name in red, 百はな

One reader of Koyama’s manga ordered her own “Momohana” uchiwa.

https://www.goodhostelskyoto.com/blog/

What’s the story behind this distinctive fan? How do Kyoto’s maiko and geiko use them? How does their display in the hanamachi create a pleasant summer mood?

Today’s blog post explores the story behind the maiko’s summer fan. We learn about their use in gift-giving, as a maiko accessory, and a sign of Kyoto. We even hear one geiko’s funny story about designing her own.

What is an uchiwa fan?

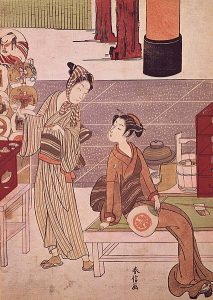

The uchiwa–a flat, round fan with a fixed handle– became a popular summer accessory in the Edo period (1603-1867).

Famous artists designed colorful prints for them. They created scenes of everyday life, portraits of famous actors and beautiful women. Many of these stylish uchiwa prints are now held in museum collections.

What is the maiko’s uchiwa called?

Kyō-maru Uchiwa 京丸うちわ

The practice of fashioning these “Round Fans of the Capital” (kyō-maru uchiwa) as the summer gift of geiko and maiko began in the early Meiji era (1868-1912).

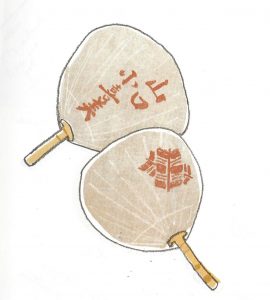

I received this uchiwa from a geiko as a gift in 2011. (Left), we see the maiko’s name, Ichimame, and her district name, Kamishichiken. (Right), we see the crest of her okiya. I photographed this in 2021 amid the greenery of North Carolina.

A Sign of Summer in Kyoto’s Hanamachi

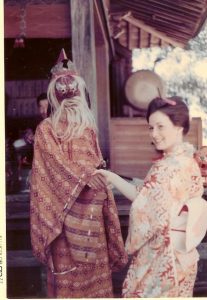

Cheerful uchiwa offer a welcome reprieve from the heat and humidity of summer in Kyoto’s hanamachi. The crisp white paper of each round, flat fan perched atop a sturdy bamboo handle bears the name of an individual geiko or maiko brushed in bright red ink.

On display in hanamachi restaurants, sweets shops, and small-goods stores, the fans signal the patronage of the local okiya. One finds uchiwa decorating tony bars and casual ramen shops alike. Shop owners hang uchiwa neatly in exacting vertical or horizontal rows or even gathered on walls like insouciant bouquets. They may cover a ceiling or wall.

Do you recognize the maiko and geiko names?

Customers familiar with the district’s geiko and maiko enjoy scanning these uchiwa displays to find names that they recognize (Aihara, 121). Dalby, too, muses, “The red characters on the white fans make an intriguing design, and as we sat down I kept glancing at them for familiar names and new ones” (31).

Making uchiwa today in Kyoto

Continuing the tradition, Komaruya, a Kyoto shop that dates to 1624, employs a team of eight to craft these distinctive fans in stages, working from a single piece of bamboo, painstakingly applying the paper, and brushing the vermillion ink. The fans feature the okiya crest (kamon) on the “front.” On the “back,” they display the name of the geiko or maiko and her hanamachi, except in the case of the Gion uchiwa which omit the district name (Aihara, 124-25).

Uchiwa as summer gifts

Koyama Aiko. Maiko-san-chi no Makanai-san. Serialized manga. Volume 10, Episode 106, p. 119. (2019).

The dresser asks Kiyo’s help with uchiwa. Koyama Aiko. Maiko-san-chi no Makanai-san. Serialized manga. Volume 10, Episode 106, p. 118. (2019).

Every June okiya mothers take charge of purchasing fresh uchiwa to send to the teahouses and shops in their district. Geiko and maiko delight in presenting them to regular clients as a form of the traditional summer gift (ochūgen), as manga artist Aiko Koyama explains in this frame.

Here, Kiyo receives an order of uchiwa for the maiko in her okiya.

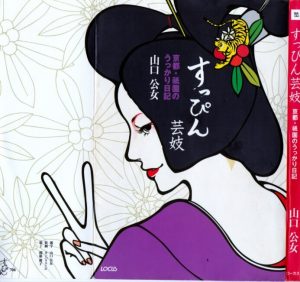

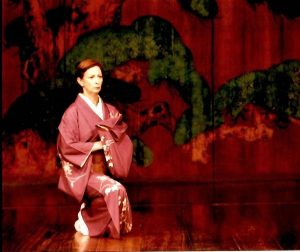

A geiko designs her own uchiwa

On becoming an independent geiko, the artist takes responsibility for providing her own uchiwa.

Gion geiko Kokimi humorously recounts her initial adventure in uchiwa design.

Following convention for a fully-fledged geiko, Kokimi needed to have her family crest on the front of the fan, and on the back, the characters for her family name Yamaguchi山口 rather than her okiya name, alongside her geiko name.

But what was Kokimi’s family crest?

Having no idea what her family crest might be, Kokimi visited Yamaguchi family graves in her native Tokunoshima.

Having no idea what her family crest might be, Kokimi visited Yamaguchi family graves in her native Tokunoshima.

There, she found something resembling an arrow that looked pretty cool. Plus, she adds with a smile, it was a crest “already in use!”

An Awesome Discovery

On receiving Kokimi’s suggested design, the uchiwa designer said he had never seen that kind of crest, but on looking it up, found that it meant “awesome arrow” (erai ya). He assured her that there was no problem with each new generation coming up with its own crest. Kokimi happily proclaims, “Hey, all you Yamaguchi out there, this is my family crest and I am going to run with it!”(141-42).

References

Aihara Kyoko, Kyoto hanamachi fasshon no bi to kokoro [The soul and beauty of Kyoto’s hanamachi fashion]. Tokyo: Tankōsha, 2011.

Dalby, Liza. Geisha. Berkeley: University of California Press,1983, 2008.

Koyama Aiko. Maiko-san-chi no Makanai-san. Serialized manga. Volume 14. Cover art. Shōgakukan, 2020, and Volume 10, Episode 106, 2019. For its new online anime adaptation, NHK World translates the manga title as Kiyo in Kyoto: From the Maiko House.

Yamaguchi Kimijo. Suppin geiko: Kyoto Gion no ukkari nikki [Bare-faced

geiko: My haphazard diary of Gion, Kyoto]. Tokyo: LOCUS , 2007

[1] The Komaruya website has lovely photos of uchiwa. http://komaruya.kyoto.jp [accessed 2 May 2018].

Jan Bardsley, “Uchiwa Summer Fans,” janbardsley.web.unc.edu, June 24, 2021