Outside Dining at Kamo River on Raised Platforms

How does Kyoto’s Kamo River become a festive site of outdoor dining in early summer? What does this mean for maiko and geiko? This post explores the custom of erecting raised yuka platforms and the changes wrought by Covid-19. Seeing these photos also takes me back to a delightful student party on the platforms, too.

What are the raised platforms 納涼床?

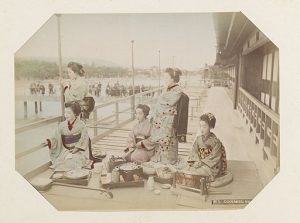

This photo shows the platforms open for outdoor seating. They extend from a row of restaurants in the Pontochō district and overlook the Kamogawa “riverbed” (kawadoko).

Japanese accounts use the term 納涼床, pronounced nōryō-yuka or nōryō-doko. Jim Breen translates this as “raised platform on the bank of a river for enjoying the summer cool.” Visiting the website of the Kyoto Kamo River Nōryō-yuka Association, I found a detailed history. Here are some highlights. (Check their site for breathtaking photos.)

Roots in the 1600s Entertainment District

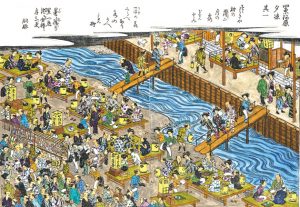

“Shijo Kawara Yusuzumi Kiitsu” by Yōzaburō Shirahata. “History of Kamo River Nouryou-yuka” 2021. https://yuka-kyoto.com/history/

The custom of enjoying the river breeze while dining outside dates back to the early 1600s when the riverbed became an entertainment district. Artist Shirahata’s print here shows people seated on mats directly on the riverbed. Wealthy clients sit on raised platforms outside the teahouses. In the mid-Edo period (1603-1867), access to riverbed seating became regulated, allowing teahouses only a limited number of outside seats. (History of Kamo River Nouryou-Yuka).

Evening Cool on the Riverbank

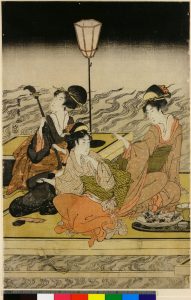

I’m re Evening Cool on the Riverbank. Utagawa Toyohiro (1773-1828). British Museum. Part of woodblock triptych.

The custom inspired artists, photographers, and writers. This ukiyo-e (woodblock print) by Utagawa Toyohiro creates a sensual nōryō-yuka scene. The river flows, the robes flow, and perhaps the sake flows, too. In Geisha (1983), Liza Dalby observes how the print shows “a geisha holding a shamisen, a maid with a kettle of sake, and a lady of pleasure on a wooden veranda over the Kamo River in the early 1800s” (50).

I’m reminded that women in the 2000s enjoy the nōryō-yuka experience for their own pleasure.

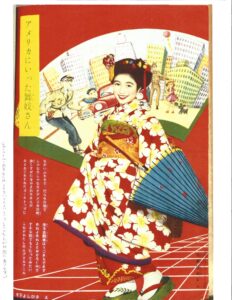

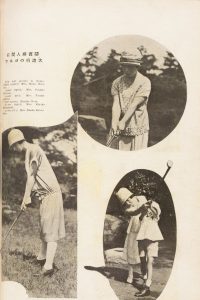

Modern Summer Festivity

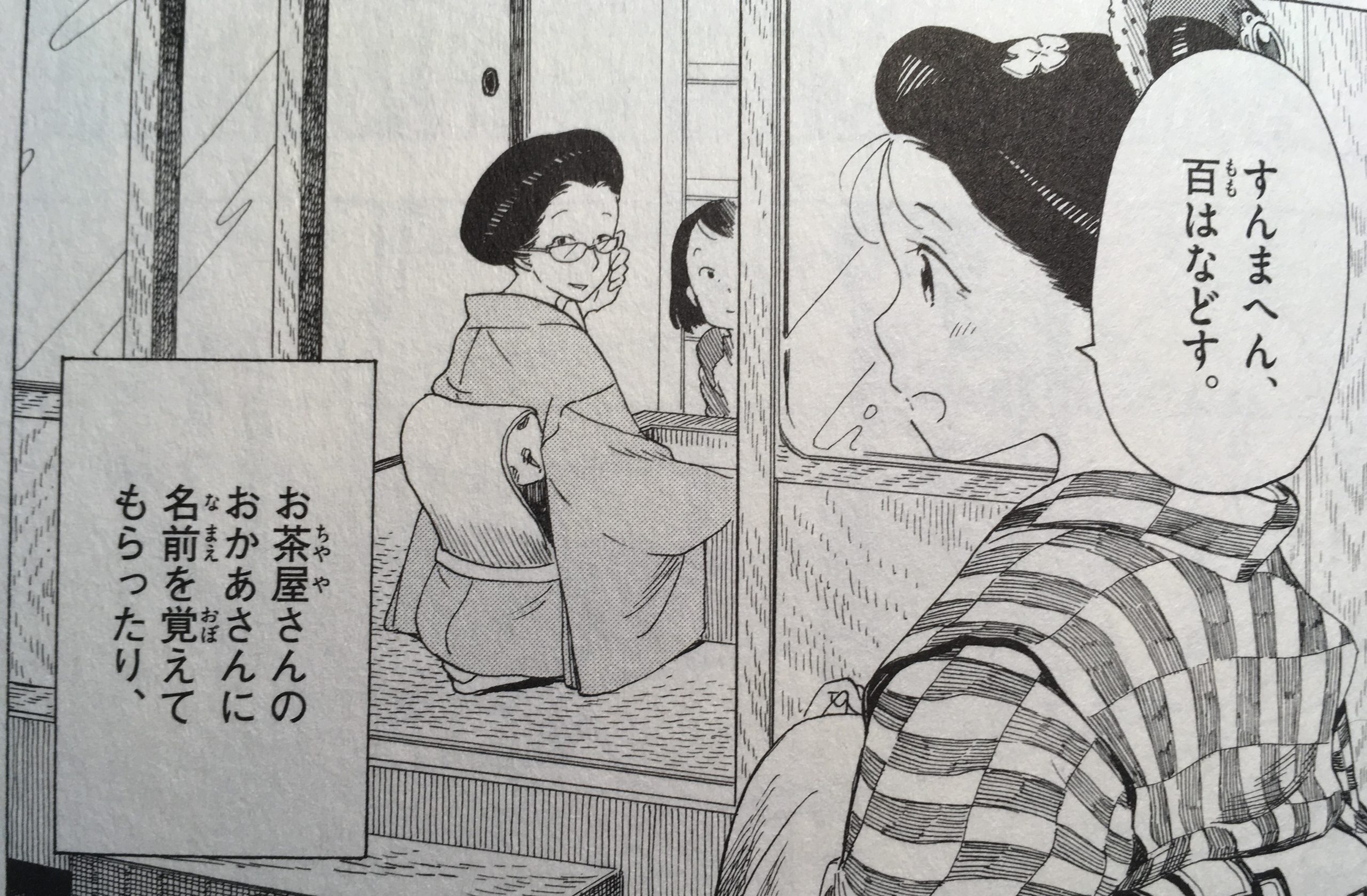

In the Meiji era (1868-1912), platforms were regularly erected in July and August. This photo features nōryō-yuka and apprentice geisha together as signs of summer leisure in Kyoto. Today, too, one may catch sight of maiko and geiko hired to attend riverside parties. Walking along the river in 2015, I happened to see a maiko’s bright hair ornament (kanzashi) through the open window of a restaurant above the platforms. One also sees many groups of young people relaxing on the riverbanks closer to the water, enjoying the experience for free, rather like the crowds that flocked there centuries ago.

A Whiff of Nostalgia in the 2000s

This 2005 daytime photo captures the look of buildings that reflect a bygone era. In 1955, 40-50 establishments sought permission to construct platforms; in 2015, over 100 did. (History of Kamo River Nouryou-Yuka).

Walking across the bridges over the Kamo River at night, one catches sight of yuka festivities. It looks like a blaze of fun!

Walking across the bridges over the Kamo River at night, one catches sight of yuka festivities. It looks like a blaze of fun!

This reminds me of a wonderful farewell party. In 2005, UNC students, our guides, teachers, and I celebrated the end of our summer study with a nōryō-yuka party. The weather was perfect. We’d become a close group. The students had worked hard, literally day and night, learning about Japanese culture, education, and theater. They attended field trips, gave class presentations, and did their own research projects. Funny, I don’t have any photos of this memorable party, but I will never forget it. I wish I could have invited a maiko to join us but that was beyond our budget.

Closed in 2020, Platforms open again in 2021

On May 1, 2021, the platforms along the Kamo River opened once again. But, with a twist–shorter hours and no alcohol–in response to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic. According to Kyoto Shinbun, the season will extend through October this year, given the warmer months of early autumn. I hope visitors enjoy this year’s nōryō-yuka safely.

References

Liza Dalby. Geisha. University of California Press, 1983; 2008.

Find a detailed history of the yuka in English and Japanese : https://www.kyoto-yuka.com/about/history.html ; In English, https://yuka-kyoto.com/

You can find an intriguing historical analysis of nōryō-yuka at RADIANT, Ritsumeikan University Research Report: Issue #7, Kyoto: http://www.ritsumei.ac.jp/research/radiant/eng/kyoto/story6.html/

Jan Bardsley, “Enjoying summer breezes at Kamo River, Kyoto,” janbardsley.web.unc.edu, May 5, 2021.