What’s the story of hanameishi 花名刺 ?

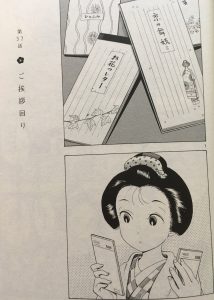

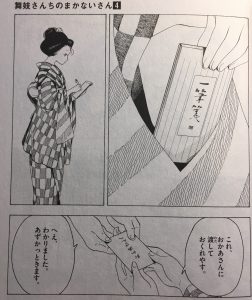

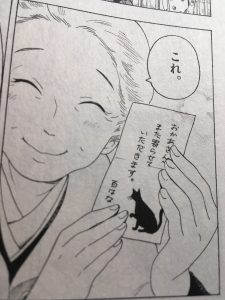

The maiko hands her guest a small card. Like other small things associated with maiko, the cheerful card evokes a sense of girlish play. A sweet souvenir, it’s also a saavy marketing tool.

What’s the story here? Today we learn about the maiko’s name card, its history, and uses.

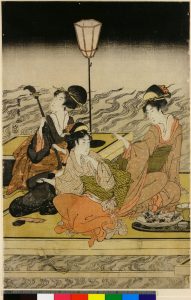

The maiko’s pretty name card

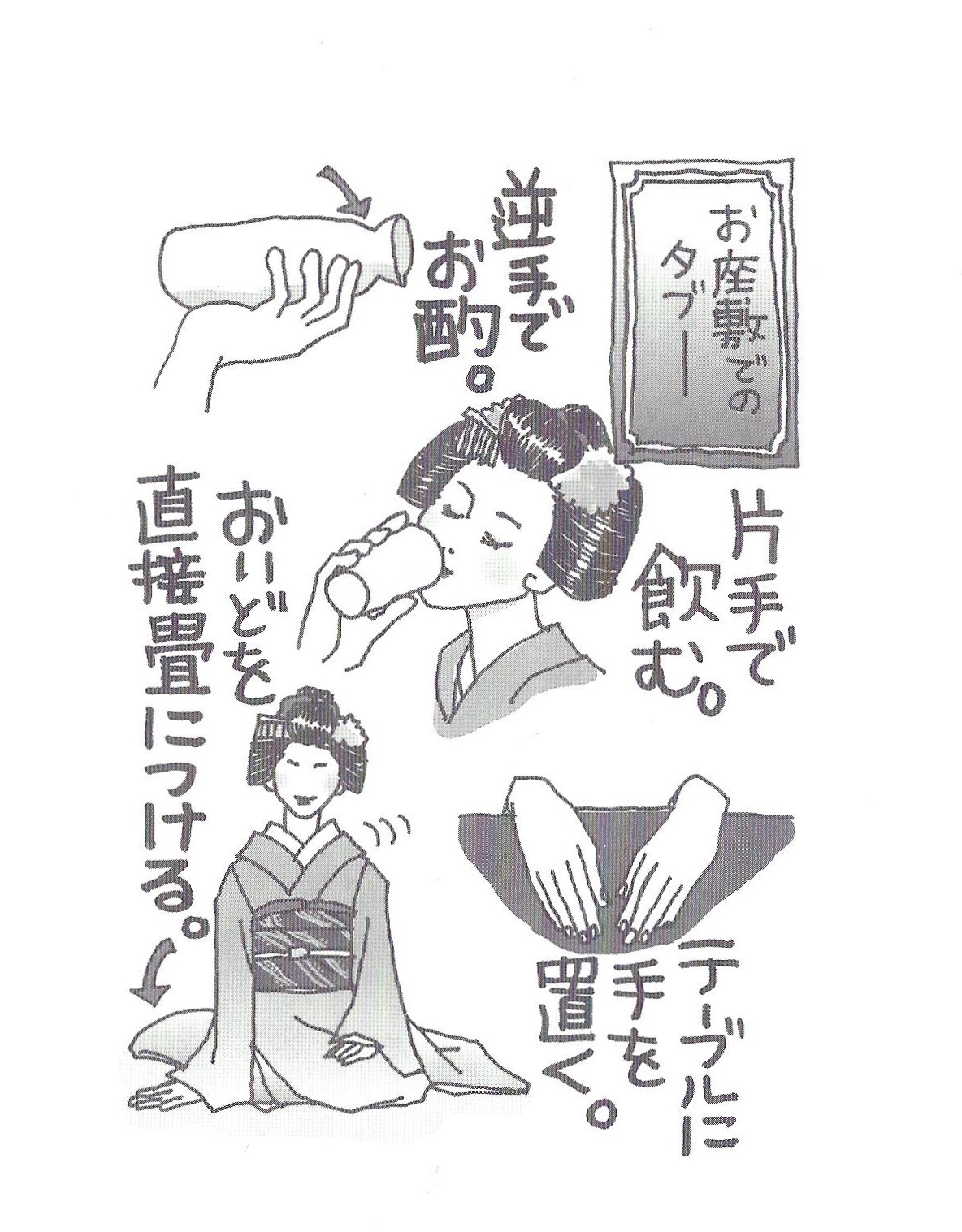

Japanese are famous for the ritual of exchanging business cards. Maiko and geisha have their own style of name cards (hanameishi, literally, flower name cards). These bear their professional name and the name of their hanamachi.

Clients should never contact maiko directly, but only ask for them through teahouse managers. That’s why these cards do not give addresses or telephone numbers. About 2.5 by 8 centimeters in size, they are smaller than the usual business card. Maiko carry their cards in pretty fabric cases.

Who created the first hanameishi?

Kyoko Aihara explains their origins. From the late Meiji period (1868-1912) through the Taishō era (1912-26), some geisha had their names printed on small, colorful match boxes. They used these as their calling cards.

Artist Matsumura Suihō (1888-1967), kimono designer and Gion aficionado, came up with the idea of creating small paper cards for maiko with playful designs. Matsumura hand-printed his cards on washi paper. His granddaughter Hayashi Hisako still makes these cards in the old style. She uses the vast storehouse of prints that Suihō created (Aihara 2011:120-23).

How do hanameishi bring good fortune?

Today hanameishi in sticker form are popular and associated with comic word play. Maiko joke that clients will profit by attaching the hanameishi to their wallets. This will inspire okane ga maikomu, that is, “money will come dancing in”— a pun on the word maiko. Geisha say that using their stickers will lead to motto maikomu, “even more money will come in,” a play on motto (more) and moto maiko (a former maiko) (Ota, et al., 2009:148, n21).

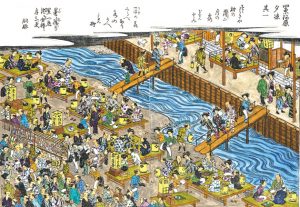

Hanameishi recall the name cards of Edo-era pilgrims

Rather than storing them in their wallets, some clients become avid hanameishi collectors. They carefully preserve them in albums. These stickers recall the ancient custom of pilgrims making name cards (senjafuda). They would stick their cards to shrines and temples to seal their good fortune. Edo-era merchants created unique woodblock-printed cards, which also were associated with humorous word-play, to exchange (kokan nōsatsu) (Salter 2006: 101-104).

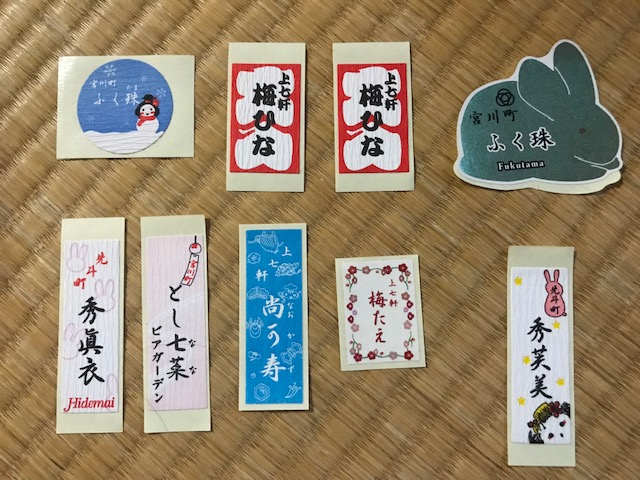

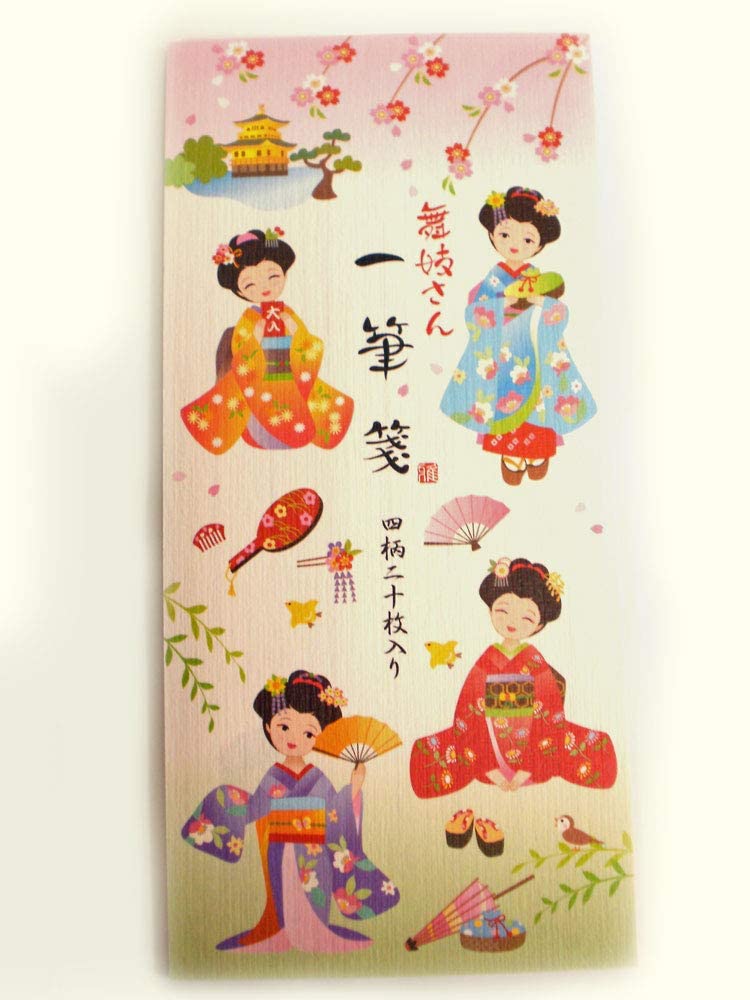

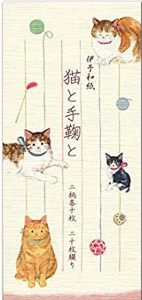

What shapes and designs do today’s name cards feature?

Maiko and geisha order different hanameishi to express the seasons. They may use as many as one thousand a year. Patterns may include signs of nature such as flowers and birds, that year’s sign of the Chinese zodiac, cute animals, and toys.

Maiko and geisha order different hanameishi to express the seasons. They may use as many as one thousand a year. Patterns may include signs of nature such as flowers and birds, that year’s sign of the Chinese zodiac, cute animals, and toys.

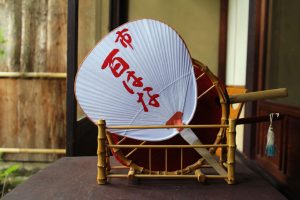

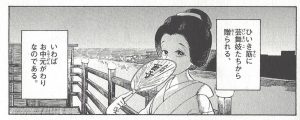

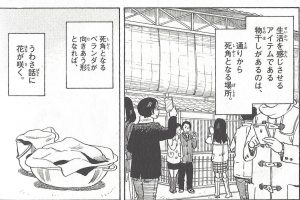

Gion geiko Kokimi designs her hanameishi with flair

Pondering the design for her newest hanameishi, geiko Kokimi asked to see what designs others were using. She was amazed at the creativity and variety. She observed that some altered the usual shape, making theirs round or square. Some signaled their favorite food or sport. Here, Kokimi’s card bears her name in vivid pink. We see Gion Kōbu’s crest top left. This is only one of many creative hanameishi used by Kokimi (Yamaguchi 2007: 102-03).

Pondering the design for her newest hanameishi, geiko Kokimi asked to see what designs others were using. She was amazed at the creativity and variety. She observed that some altered the usual shape, making theirs round or square. Some signaled their favorite food or sport. Here, Kokimi’s card bears her name in vivid pink. We see Gion Kōbu’s crest top left. This is only one of many creative hanameishi used by Kokimi (Yamaguchi 2007: 102-03).

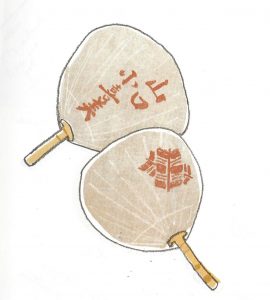

An artful design from Miyagawa-chō

This hanameshi comes from Ikuda Takeda (Koito), who leads the Kaden okiya. We see the district name at the top (Miyagawa-chō) and the name Kaden within the folded paper design. The folded paper recalls koibumi, the Japanese love letter, that we explored last week.

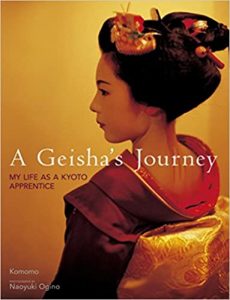

You can read about the maiko’s life at Kaden in A Geisha’s Journey. Photographer Naoyuki Ogino collaborated with former maiko, now geiko Komomo, for nine years. His photographs of her daily life at Kaden and Komomo’s own account reveal the rigor and fun of maiko life in the 2000s.

Create or order your own hanameishi

Hanameishi are not the sole preserve of geiko and maiko. Teenagers enjoy printing their own inexpensively at Kyoto game centers. You can also order maiko-style name cards from specialty shops; I found one online. The National Saturday Club offers a wonderful online tutorial and template, Design a Japanese Senjafuda.

REFERENCES

Aihara Kyoko, Kyoto hanamachi fasshon no bi to kokoro [The soul and beauty of Kyoto’s hanamachi fashion]. Tokyo: Tankōsha, 2011.

Komomo and Naoyuki Ogino. A Geisha’s Journey: My Life as a Kyoto Apprentice. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 2008.

Ōta Tōru and Hiratake Kōzō, eds. Kyō no kagai: Hito, waza, machi [Kyoto’s hanamachi: People, arts, towns]. Tokyo: Nippon Hyōronsha, 2009.

Salter, Rebecca. Japanese Popular Prints: From Votive Slips to Playing Cards. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2006.

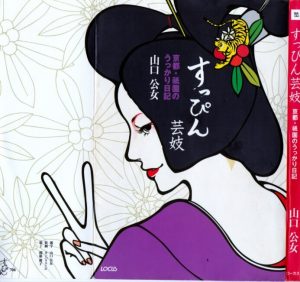

Yamaguchi Kimijo. Suppin geiko: Kyoto Gion no ukkari nikki [Bare-faced

geiko: My haphazard diary of Gion, Kyoto]. Tokyo: LOCUS, 2007

Jan Bardsley, “Hanameishi: The Maiko’s Cheerful Name Card,” Janbardsley.web.unc.edu. August 19, 2021