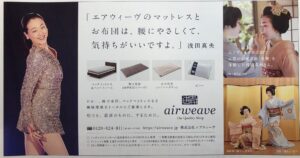

Wasn’t that the Olympic figure skater Asada Mao?

What was she doing in maiko masquerade?

This ad in my Miyako Odori 2019 dance program caught me by surprise. What was the story here? As I explore in today’s post, this famous Japanese athlete in maiko garb invites us to think about performances of femininity in sports, dance, and costuming.

The World Champion as Girl Next Door

Asada was 29 in 2019, almost a decade older than the oldest maiko. But her small frame, apparent youth and innocence, and her “girl next door” persona made Asada a good fit for role-playing as Kyoto’s quintessential girl. As it turns out, Asada has role-played as a maiko in previous commercials set in Kyoto. Her maiko masquerade is never a trick, though. Rather, these performances invite viewers to contemplate the transformation of the national sports icon as a maiko. (As I explain in Maiko Masquerade, media often portray the maiko as an “ordinary girl” transformed).

Asada has maiko make-up applied for the August 17, 2014 SMILE event at Kyoto Takashimaya. http://maoasada.jp/mao/event/

In 2014, the department store Takashimaya launched SMILE, an exhibit in honor of Asada Mao. The exhibit, which traveled to various Takashimaya stores in Japan, attracted over 600,000 visitors (Asahi Shimbun). When in Kyoto for SMILE, Asada did another turn as a maiko.

But let’s not forget the fierce athlete on ice

Certainly, there is more to this hard-driving Olympic athlete than her pretty costumes suggest. In his insightful Diva Nation chapter, “Ice Princess: Asada Mao the Demure Diva,” Masafumi Monden looks beyond the compliant good girl persona to examine Asada’s strengths and ambition. He argues that, “Asada consciously or otherwise uses her demure, good girl persona to allow the exercise of the ego and power of a diva without attracting criticism, in a subtle, effective, and notably Japanese fashion.”

Mao Asada during her long program at the 2013 World Championships. Photo David W. Carmichael

Wikimedia Commons

Born in Nagoya Prefecture in 1990, Asada Mao was already a graceful ballerina when she tried ice skating to boost her dance skills. As a teen, Asada earned fame for her ability to land the risky triple axel and triple-triple jumps. In 2010, she won a silver medal at the Vancouver Winter Olympics. Monden explains, “Asada is surely one of the few women skaters whose technical proficiency rivals that of men.”

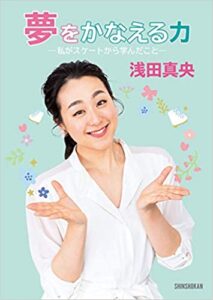

The winner of multiple championships, Asada became a national icon, managing to blend her obvious diligence, skill, and sportsmanship with a feminine, modest persona. Her good manners won Asada praise abroad, too. Monden shows how she asserts herself in making career choices, never losing fans. “Asada’s popularity in Japan is massive….[she] claimed the top slot in the ranking of most successful female athletes in 2015.”

Asada’s regular feats on the rink astonished spectators, exemplifying “the diva [who] takes risks.”

In April 2017, Asada retired from figure skating. She continues to take an active public role. Asada participates in charity events, makes commercials, and publishes books. She maintains an official website and blog in Japanese:http://mao-asada.jp/

What Asada Mao tells us about maiko & geiko

Asada Mao’s determination, athleticism, and ability to manage her public persona make us take another look at Kyoto’s maiko and geiko. Devoting themselves to strenuous dance practice, performing as the city’s celebrities, and modeling Japanese etiquette take work. It’s tempting to see Asada and the maiko’s femininity performances as masquerades given their obvious personal strengths, even a disguise of female ambition that makes it more acceptable. But we can also consider these divas as redefining the feminine. Monden sees Asada as “an icon who demonstrates the potential of a new kind of divahood, as a young diva who gets her own way and refuses to give in, but in a polite, upright amicable way that wins people’s hearts.”

Asada dancing with the geiko

On Aug. 17, 2014, Asada posted photos of herself costumed as a maiko for the Kyoto Takashimaya SMILE exhibit. http://mao-asada.jp/mao/event/

The summer fan displays her name, Mao.

Let’s close with a clip of Asada Mao visiting Kyoto posted in 2015 that Masafumi Monden passed on to me.

The clip shows Asada approaching the famous Gion teahouse Tomiyo. Here, she observes a Gion geiko, also named Mao, dancing. The jikata (musician) Danyū plays the samisen. Then, Asada takes her first lesson in Kyōmai dance from Inoue Yasuko, daughter of dance master Inoue Yachiyo V. Next Asada costumes as a maiko. Now, she’s ready for her dance performance with geiko Mao! Since the video ends with a night’s rest on an Airweave mattress, we might conclude the event is staged as a commercial. But this clip is more than a fanciful mattress ad–it shows the difficulty of maiko dance, the practiced skill of the geiko, and even champion athlete Asada struggling to learn it.

I come away with admiration for the skills of both the dancer and the skater.

References

Masafumi Monden. “Ice Princess: Asada Mao the Demure Diva,” in Laura Miller and Rebecca Copeland, eds. Diva Nation: Female Icons from Japanese Cultural History. Oakland: University of California Press, 2018.

Jan Bardsley, “Asada Mao: Olympic Skater in Maiko Masquerade,” Janbardsley.web.unc.edu. March 15, 2021