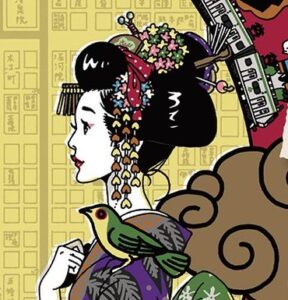

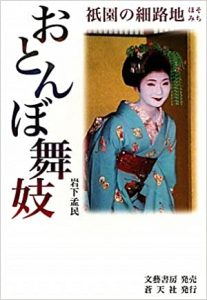

The Gion maiko Chiyofuku looks intent here as she carefully brushes color on her lips. Artist Hashiguchi Goyō (1880-1921) created Woman Holding a Lip Brush in 1920. His print makes me curious about this cosmetic moment. In English, should we say that this maiko wears lip coloring or lipstick? What’s the difference? How can prints from the 1920s and 1930s help us appreciate maiko makeup today?

The Difference between Lip Coloring and Lipstick

I found Goyō’s print in the fascinating book, The Women of Shin Hanga, edited by Allen Hockley. He defines shin hanga (new print) as a movement spanning the 1910s to the 1950s that “revitalized the traditional Japanese art of woodblock printing” (Introduction). Many of the prints show women with bright red lips. They draw our attention to public and private cosmetic moments.

“Western scholars inaccurately substitute ‘lipstick’ for benifude.”

But, as Hockley observes, “Western scholars inaccurately substitute ‘lipstick’ for benifude. Lipstick is a term specific to the tubular applicator used in Western makeup. A benifude refers to the fude (brush) used to apply kuchi-beni, the term for beni (red/pink) lip coloring ” (138, note 1). Aha! Goyō’s model is wearing lip coloring.

Interesting! I never thought about lipstick as defined by its applicator–only as a product that colored the lips. But these modern Japanese prints make clear that ‘lipstick’ was a distinctly new kind of tool. And they make us look more carefully at the benifude used by maiko. Remember when we saw star skater Asada Mao costumed as a maiko? Note the geisha brushes on her lip coloring.

Asada has maiko make-up applied for the August 17, 2014 SMILE event at Kyoto Takashimaya. http://mao-asada.jp/mao/event/

Capturing Cosmetic Moments Private and Public

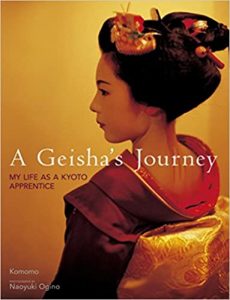

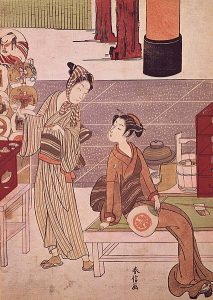

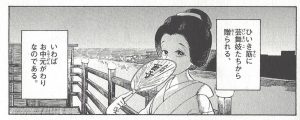

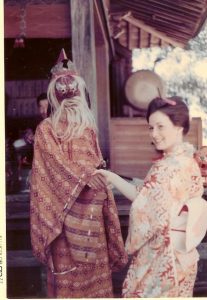

Many contemporary photo books and films show maiko applying makeup before heading to the evening’s ozashiki. They sit before a small, low table of pots and brushes. A magical assemblage, these cosmetics create the aura of old-fashioned elegance. We see the “ordinary girl” of the 2000s about to transform herself into a figure of the past in the present.

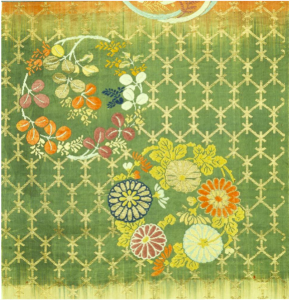

This 1930 print Cotton Kimono with Japanese Iris Pattern by Torii Kotondo (1900-1976), another in The Women of Shin Hanga fascinates viewers in the same way. We learn how viewers would have been attracted to this “depiction of the array of paints and powders that constitute Japanese makeup and the various brushes used to apply them” (208).

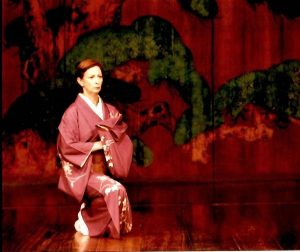

At the same time, we find prints of women in the 1930s using modern lipstick. For example, let’s look at the 1931 print No. 6 Lipstick (Roku: Kuchibeni) in the series Modern Fashions by Kobayakawa Kiyoshi (1889-1948). Hockley observes that while “she wears traditional dress, her permed hair with curls falling around her face, her lipstick, clutch purse with hand mirror, ring, and wristwatch indicate her modern girl affiliations” (220). He notes that even though the print’s title uses the term kuchibeni, unlike Goyō’s 1920 maiko, this woman “uses lipstick from a modern applicator” (220).

What is Kuchibeni?

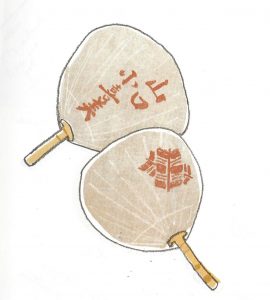

In her excellent book, Geisha: A Living Tradition, Kyoko Aihara explains that this lip color “comes in a small stick that is melted in water after which crystallized sugar is then added to give the cosmetic lustre” (77). In Guide to Maiko Accessories, Aihara writes that when a maiko carries kuchibeni in her handbag, it’s stored in a small container. She brings along a spray container of water to use to soften it (86).

Aihara notes, “Originally, the rouge was stored in a pretty painted clamshell of the kind that is now sold as a souvenir in Kyoto ” (1999: 77).

The Millennial Maiko Ichimame Wears Lipstick too

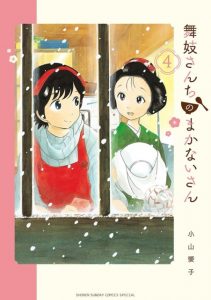

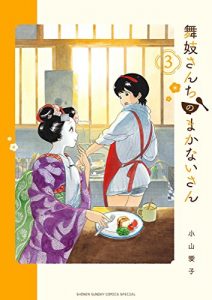

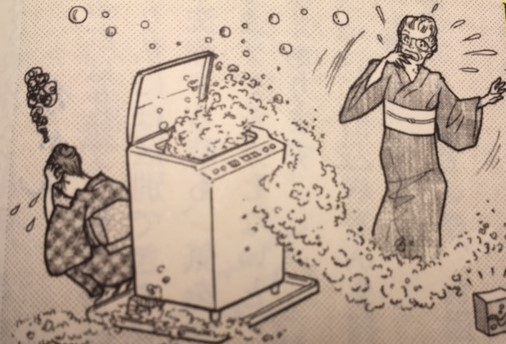

In her book Maiko Etiquette, Ichimame (featured in my book Maiko Masquerade) talks about changing her makeup to fit her outfit. Katsuyama Keiko illustrates.

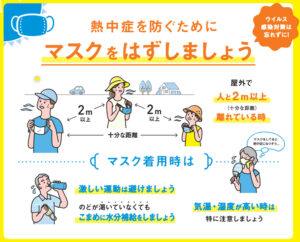

The black-and-white graphic shows her “maiko-san’s makeup.” This is her formal look, so she wears kuchibeni. Next to the mascara wand at the lower right, we see the images of the “water-soluble” beni and lip brush.

Turning to the color image, we see Ichimame dressed more simply to go to her dance lessons. Here, she wears a light pink MAC lipstick and lip cream (39). She also wears sun screen.

Illustrations of Ichimame’s makeup convey the spirit of her own times. But they read like a visual guide to the maiko’s makeup for girl readers. There’s a sense of transformation and play here. We learn that Ichimame, a maiko in 2007, wears lip coloring and lipstick to suit her looks. Thanks to this brief foray into Shin Hanga, I understand the difference.

REFERENCES

Aihara, Kyoko. Geisha: A Living Tradition. London: Carlton Books, 1999; Maiko-san no odōgu-chō [Guide to maiko accessories]. Tokyo: Sankaidō, 2007.

Hockley, Allen, Kendall H. Brown, Nozomi Naoi, and Allen Hockley. The Women of Shin Hanga: The Judith and Joseph Barker Collection of Japanese Prints. Hanover, New Hampshire : Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, 2013.

Kamishichiken Ichimame. Maiko Etiquette. Tokyo: Daiwa Shobō, 2007. Illustrated by Katsuyama Keiko.

For more on women in Shin Hanga and many more images, see “The Female Image in Shin Hanga Prints” at Haverford Libraries:

https://ds-omeka.haverford.edu/japanesemodernism/exhibits/show/the-female-image-in-shin-hanga

Jan Bardsley, “The Maiko’s Look: Lipstick or Lip Coloring?,” Janbardsley.web.unc.edu. August 27, 2021.