Maiko turn up in Kyoto as all kinds of small things.

How does that affect their public persona?

Maiko keychains, stickers, cell-phone straps, and tiny candies abound in souvenir shops—a veritable cornucopia of girlish delights. Uniformly bright, perky, and inexpensive, they fit easily in your pocket. Portable talismans of kawaii, like Hello Kitty goods, they bring a dash of charm to daily routines.

But Hello Kitty is a fiction. Maiko are real people. So, how do these charming “small things” help define the public image of the maiko herself? Three aspects stand out.

1.Maiko are childlike.

Many souvenir maiko look cherubic. This recalls how maiko of the 1920s and 1930s really were children, sometimes as young as eleven. Now maiko trainees (shikomi) must be at least fifteen years old. Still, an air of girlish innocence remains essential to the maiko’s appeal. In Maiko Masquerade, I discuss how some maiko find “living down” to this naivete constraining, while others feel free in their girl role.

Of course, even ferocious characters like Godzilla can become childlike as plastic toys. The maiko’s girlish persona makes the transformation especially easy.

2. Maiko are kawaii.

The maiko defines a certain stripe of kawaii. The kind of kawaii that sits at “the juncture of ‘cute,’ ‘tiny,’ or ‘lovable” (Merriam-Webster). According to scholar Joshua Paul Dale, kawaii things convey the “unabashed joy found in the undemanding presence of innocent, harmless, adorable things.”

While “kawaii” encompasses different registers, including the grotesque and creepy, maiko kawaii embraces this sense of “unabashed joy.”

Travel and fashion guides portray the maiko, too, as a fan of kawaii things. She likes bite-size sushi and colorful fruit sandwiches. She may carry Minnie Mouse or Hello Kitty goods in her handbag. In the Kyoto visual field, the kawaii maiko and her adorable souvenir likeness blend to produce an aura of charm.

As Kyoto girl and Kyoto souvenir, the maiko lightens the cultural weight of ancient temples, gardens, and Zen-inspired arts. Transferred into countless small objects, the maiko makes Kyoto accessible and consumable. Yet, as Kyoto’s mascot, the maiko continually reminds tourists that they are in the old capital.

3. Maiko make Kyoto a girls’ playground.

Charming maiko goods, kawaii maiko images recreate Kyoto as a leisure space friendly to girls and women. While the historical maiko emerged, too, in a world of play for purchase, it was a world geared to providing pleasure to Japanese men. Contemporary maiko and their souvenir look-alikes, however, shift the concern from pleasing men to inviting girls to have fun. Girlish play extends into all kinds of small consumables and sweet experiences. Crossing gender boundaries, tourists of all sexes today may enjoy the invitation to have fun.

The maiko trinkets on my desk and bookcase always make me smile. Maybe they’re telling me to relax and enjoy the moment.

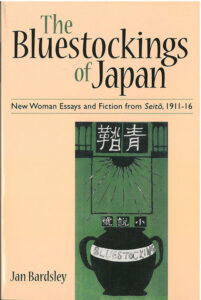

Jan Bardsley, “Maiko and the Charm of Small Things,” janbardsley.web.unc.edu. March 22, 2021.